Medical term:

Endometriosis

Endometriosis

Definition

Description

Causes and symptoms

- Implantation theory. Originally proposed in the 1920s, this theory states that a reversal in the direction of menstrual flow sends discarded endometrial cells into the body cavity where they attach to internal organs and seed endometrial implants. There is considerable evidence to support this explanation. Reversed menstrual flow occurs in 70-90% of women and is thought to be more common in women with endometriosis. However, many women with reversed menstrual flow do not develop endometriosis.

- Vascular-lymphatic theory. This theory suggests that the lymph system or blood vessels (vascular system) is the vehicle for the distribution of endometrial cells out of the uterus.

- Coelomic metaplasia theory. According to this hypothesis, remnants of tissue left over from prenatal development of the woman's reproductive tract transforms into endometrial cells throughout the body.

- Induction theory. This explanation postulates that an unidentified substance found in the body forces cells from the lining of the body cavity to change into endometrial cells.

- Heredity. A woman's chance of developing endometriosis is seven times greater if her mother or sisters have the disease.

- Immune system function. Women with endometriosis may have lower functioning immune systems that have trouble eliminating stray endometrial cells. This would explain why a high percentage of women experience reversed menstrual flow while relatively few develop endometriosis.

- Dioxin exposure. Some research suggests a link between the exposure to dioxin (TCCD), a toxic chemical found in weed killers, and the development of endometriosis.

- Menstrual pain. Pain in the lower abdomen that begins a day or two before the menstrual period starts and continues through to the end is typical of endometriosis. Some women also report lower back aches and pain during urination and bowel movement, especially during their periods.

- Painful sexual intercourse. Pressure on the vagina and cervix causes severe pain for some women.

- Abnormal bleeding. Heavy menstrual periods, irregular bleeding, and spotting are common features of endometriosis.

- Infertility. There is a strong association between endometriosis and infertility, although the reasons for this have not been fully explained. It is thought that the build up of scar tissue and adhesions blocks the fallopian tubes and prevents the ovaries from releasing eggs. Endometriosis may also affect fertility by causing hormonal irregularities and a higher rate of early miscarriage.

Diagnosis

Treatment

Pain relief

Hormonal treatments

- Oral contraceptives. Continuously taking estrogen-progestin pills tricks the body into thinking it is pregnant. This state of pseudopregnancy means reduced pelvic pain and a temporary withering of endometrial implants.

- Danazol (Danocrine) and gestrinone are synthetic male hormones that lower estrogen levels, prevent menstruation, and shrink endometrial tissues. On the downside, they lead to weight gain and menopause-like symptoms, and cause some women to develop masculine characteristics.

- Progestins. Medroxyprogesterone (Depo-Provera) and related drugs may also be used in treating endometriosis. They have been proven effective in minimizing pain and halting the progress of the condition, but are rarely used because of the high rate of side effects.

- Gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnHR) agonists. These estrogen-inhibiting drugs successfully limit pain and prevent the growth of endometrial implants. They can cause menopause symptoms, however, and doses have to be regulated to prevent bone loss associated with low estrogen levels.

Surgery

Alternative treatment

Prognosis

Prevention

Resources

Organizations

Key terms

endometriosis

[en″do-me″tre-o´sis]

en·do·me·tri·o·sis

(en'dō-mē'trē-ō'sis), [MIM*131200]endometriosis

(ĕn′dō-mē′trē-ō′sĭs)endometriosis

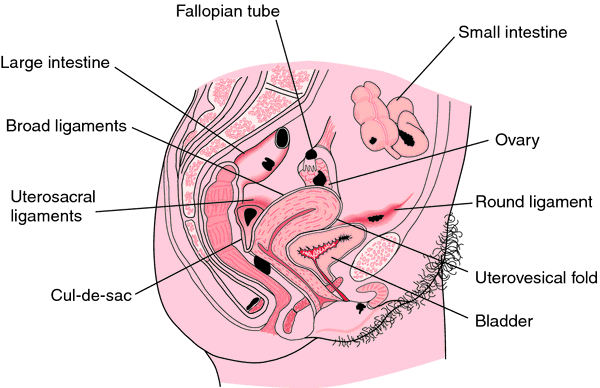

A condition affecting up to 50% of women, which is defined as the presence of functioning endometrial glands and stroma outside of uterine cavity, occurring (in descending order of frequency) in: ovaries, broad ligaments, rectovaginal septum, umbilical scars, intestine, lungs, breast; laparoscopic resection or ablation of minimal lesions increased fecundity.Clinical findings

Often accompanied by dysmenorrhoea, cyclical pain, low back pain, thigh pain, hypermenorrhoea, repeated miscarriages, infertility, bleeding per rectum or bladder. Regional swelling with vicarious ectopic bleeding parallels menses.

Evaluation

Laparoscopy.

Management

Surgery if anatomy is distorted; TAH-BSO is definitive therapy.

Prognosis

Endometriosis is associated with future development of cancer.

Malignancy in endometriosis

Malignancy can arise in the epithelium (e.g., clear-cell or endometrioid carcinomas), stroma (e.g., endometrial stromal sarcoma, MMMT, adenosarcoma), or in other lesions (e.g., borderline tumours, endometrioid adenofibroma). Cancer allegedly occurs in up to 10% of cases.

Endometriosis, criteria and comments

Glands

• Active (functional) or inactive.

• Metaplastic changes—ciliated, hobnail, mucinous or squamous.

Stroma

• Usually readily apparent.

• May be inconspicuous cuff.

• Spiral arterioles, haemosiderin, CD10.

• Decidualisation.

• Myxoid change.

• Smooth muscle metaplasia/elastosis.

Haemosiderin

• Pigmented histiocytes.

• Pseudoxanthomatous.

endometriosis

Endometrial implants Gynecology A condition affecting up to 50% of ♀, defined as the presence of functioning endometrial glands and stroma outside of uterine cavity, occurring, in descending order of frequency, the ovaries, broad ligaments, rectovaginal septum, umbilical scars, intestine, lungs, etc Clinical Often accompanied by dysmenorrhea, cyclical pain, low back pain, thigh pain, hypermenorrhea, repeated miscarriages, infertility; bleeding per rectum or bladder; regional swelling with vicarious ectopic bleeding parallels menses Evaluation Laparoscopy Management Surgery if anatomy is distorted; TAH-BSO is definitive therapy; laparoscopic resection or ablation of minimal lesions ↑ fecundity ♀en·do·me·tri·o·sis

(en'dō-mē-trē-ō'sis)endometriosis

(en?do-me?tre-o'sis ) [ endo- + ¹metro- + osis]

Etiology

Although the cause is unknown, hypotheses are that either endometrial cell migration occurs during fetal development, or the cells shed during menstruation are expelled through the fallopian tubes to the peritoneal cavity.

Symptoms

No single symptom is diagnostic. Patients often complain of dysmenorrhea with pelvic pain, premenstrual dyspareunia, sacral backache during menses, and infertility. Dysuria may indicate involvement of the urinary bladder. Cyclic pelvic pain, usually in the lower abdomen, vagina, posterior pelvis, and back, begins 5 to 7 days before menses, reaches a peak, and lasts 2 to 3 days. Premenstrual tenesmus and diarrhea may indicate lower bowel involvement. Dyspareunia may indicate involvement of the cul-de-sac or ovaries. No correlation exists between the degree of pain and the extent of involvement; many patients are asymptomatic.

Diagnosis

Although history and findings of physical examination may suggest endometriosis, and imaging studies (transvaginal ultrasound) may be helpful, definitive diagnosis of endometriosis and staging requires laparoscopy, a procedure that allows direct visualization of ectopic lesions and biopsy.

Treatment

Medical and surgical approaches may be used to preserve fertility and to increase the woman's potential for achieving pregnancy. Pharmacological management includes the use of hormonal agents to induce endometrial atrophy by maintaining a chronic state of anovulation.

Surgical management includes laparotomy, lysis of adhesions, laparoscopy with laser vaporization of implants, laparotomy with excision of ovarian masses, or total hysterectomy with bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy and removal of aberrant endometrial cysts and implants to encourage fertility. The definitive treatment for endometriosis ends a woman's potential for pregnancy by removal of the uterus, tubes, and ovaries.

Patient care

Providing emotional support and meeting informational needs are major concerns. The patient is encouraged to verbalize feelings and concerns.

The woman is prepared physically and emotionally for any surgical procedure.

Adolescent girls with a narrow vagina or small vaginal meatus are advised to use sanitary napkins rather than tampons to help prevent retrograde flow. Because infertility is a possible complication of endometriosis, a patient who wants children is advised not to postpone childbearing. An annual pelvic examination and Papanicolaou test are recommended.

peritoneal endometriosis

thoracic endometriosis

transplantation endometriosis

endometriosis

Location at abnormal sites of the glandular and blood-vessel-containing (vascularized) lining tissue of the womb (the ENDOMETRIUM). Endometrial tissue may occur in the Fallopian (uterine) tubes, on the ovaries, within the muscle wall of the womb, anywhere in the pelvis, or even at remoter sites. All endometrial tissue is subject to the hormones that control the menstrual cycle and follows the same sequence of changes that affects the womb lining. Blood produced at these abnormal sites cannot usually escape and there is local pressure and pain with each menstrual period. A large cyst can form in an ovary.Patient discussion about endometriosis

Q. Will my daughter have endometriosis also? I was diagnosed with endometriosis when I was 15. Now, 15 years and many efforts later I finally have an adorable baby girl. Because I had such a bad experience with endometriosis, I'm a little worried- will she have endometriosis too? Is it genetic? Can I do something to prevent it?

Q. Can you get rid of endometriosis?

Latest Searches:

Voraxaze - Voranil - Voorhoeve - voodoo - VOO - Vontrol - von - vomitus - vomiturition - vomitory - vomitoria - vomito - vomitive - vomiting - vomit - vomica - vomerovaginalis - vomerovaginal - vomerorostralis - vomerorostral -

- Service manuals - MBI Corp