Pneumonia

Definition

Pneumonia is an infection of the lung that can be caused by nearly any class of organism known to cause human infections. These include bacteria, amoebae, viruses, fungi, and parasites. In the United States, pneumonia is the sixth most common disease leading to death; 2 million Americans develop pneumonia each year, and 40,000-70,000 die from it. Pneumonia is also the most common fatal infection acquired by already hospitalized patients. In developing countries, pneumonia ties with diarrhea as the most common cause of death. Even in nonfatal cases, pneumonia is a significant economic burden on the health care system. One study estimates that people in the American workforce who develop pneumonia cost employers five times as much in health care as the average worker.

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), however, the number of deaths from pneumonia in the United States has declined slightly since 2001.

Description

Anatomy of the lung

To better understand pneumonia, it is important to understand the basic anatomic features of the respiratory system. The human respiratory system begins at the nose and mouth, where air is breathed in (inspired) and out (expired). The air tube extending from the nose is called the nasopharynx. The tube carrying air breathed in through the mouth is called the oropharynx. The nasopharynx and the oropharynx merge into the larynx. The oropharynx also carries swallowed substances, including food, water, and salivary secretion, which must pass into the esophagus and then the stomach. The larynx is protected by a trap door called the epiglottis. The epiglottis prevents substances that have been swallowed, as well as substances that have been regurgitated (thrown up), from heading down into the larynx and toward the lungs.

A useful method of picturing the respiratory system is to imagine an upside-down tree. The larynx flows into the trachea, which is the tree trunk, and thus the broadest part of the respiratory tree. The trachea divides into two tree limbs, the right and left bronchi. Each one of these branches off into multiple smaller bronchi, which course through the tissue of the lung. Each bronchus divides into tubes of smaller and smaller diameter, finally ending in the terminal bronchioles. The air sacs of the lung, in which oxygen-carbon dioxide exchange actually takes place, are clustered at the ends of the bronchioles like the leaves of a tree. They are called alveoli.

The tissue of the lung which serves only a supportive role for the bronchi, bronchioles, and alveoli is called the lung stroma.

Function of the respiratory system

The main function of the respiratory system is to provide oxygen, the most important energy source for the body's cells. Inspired air (the air you breath in) contains the oxygen, and travels down the respiratory tree to the alveoli. The oxygen moves out of the alveoli and is sent into circulation throughout the body as part of the red blood cells. The oxygen in the inspired air is exchanged within the alveoli for the waste product of human metabolism, carbon dioxide. The air you breathe out contains the gas called carbon dioxide. This gas leaves the alveoli during expiration. To restate this exchange of gases simply, you breathe in oxygen, you breathe out carbon dioxide

Respiratory system defenses

The healthy human lung is sterile. There are no normally resident bacteria or viruses (unlike the upper respiratory system and parts of the gastrointestinal system, where bacteria dwell even in a healthy state). There are multiple safeguards along the path of the respiratory system. These are designed to keep invading organisms from leading to infection.

The first line of defense includes the hair in the nostrils, which serves as a filter for large particles. The epiglottis is a trap door of sorts, designed to prevent food and other swallowed substances from entering the larynx and then trachea. Sneezing and coughing, both provoked by the presence of irritants within the respiratory system, help to clear such irritants from the respiratory tract.

Mucus, produced through the respiratory system, also serves to trap dust and infectious organisms. Tiny hair like projections (cilia) from cells lining the respiratory tract beat constantly. They move debris trapped by mucus upwards and out of the respiratory tract. This mechanism of protection is referred to as the mucociliary escalator.

Cells lining the respiratory tract produce several types of immune substances which protect against various organisms. Other cells (called macrophages) along the respiratory tract actually ingest and kill invading organisms.

The organisms that cause pneumonia, then, are usually carefully kept from entering the lungs by virtue of these host defenses. However, when an individual encounters a large number of organisms at once, the usual defenses may be overwhelmed, and infection may occur. This can happen either by inhaling contaminated air droplets, or by aspiration of organisms inhabiting the upper airways.

Conditions predisposing to pneumonia

In addition to exposure to sufficient quantities of causative organisms, certain conditions may make an individual more likely to become ill with pneumonia. Certainly, the lack of normal anatomical structure could result in an increased risk of pneumonia. For example, there are certain inherited defects of cilia which result in less effective protection. Cigarette smoke, inhaled directly by a smoker or second-hand by a innocent bystander, interferes significantly with ciliary function, as well as inhibiting macrophage function.

Stroke, seizures, alcohol, and various drugs interfere with the function of the epiglottis. This leads to a leaky seal on the trap door, with possible contamination by swallowed substances and/or regurgitated stomach contents. Alcohol and drugs also interfere with the normal cough reflex. This further decreases the chance of clearing unwanted debris from the respiratory tract.

Viruses may interfere with ciliary function, allowing themselves or other microorganism invaders (such as bacteria) access to the lower respiratory tract. One of the most important viruses is HIV (Human Immunodeficiency virus), the causative virus in AIDS (acquired immunodeficiency syndrome). In recent years this virus has resulted in a huge increase in the incidence of pneumonia. Because AIDS results in a general decreased effectiveness of many aspects of the host's immune system, a patient with AIDS is susceptible to all kinds of pneumonia. This includes some previously rare parasitic types which would be unable to cause illness in an individual possessing a normal immune system.

The elderly have a less effective mucociliary escalator, as well as changes in their immune system. This causes this age group to be more at risk for the development of pneumonia.

Various chronic conditions predispose a person to infection with pneumonia. These include asthma, cystic fibrosis, and neuromuscular diseases which may interfere with the seal of the epiglottis. Esophageal disorders may result in stomach contents passing upwards into the esophagus. This increases the risk of aspiration into the lungs of those stomach contents with their resident bacteria. Diabetes, sickle cell anemia, lymphoma, leukemia, and emphysema also predispose a person to pneumonia.

Genetic factors also appear to be involved in susceptibility to pneumonia. Certain changes in DNA appear to affect some patients' risk of developing such complications of pneumonia as septic shock.

Pneumonia is also one of the most frequent infectious complications of all types of surgery. Many drugs used during and after surgery may increase the risk of aspiration, impair the cough reflex, and cause a patient to underfill their lungs with air. Pain after surgery also discourages a patient from breathing deeply enough, and from coughing effectively.

Radiation treatment for breast cancer increases the risk of pneumonia in some patients by weakening lung tissue.

Causes and symptoms

The list of organisms which can cause pneumonia is very large, and includes nearly every class of infecting organism: viruses, bacteria, bacteria-like organisms, fungi, and parasites (including certain worms). Different organisms are more frequently encountered by different age groups. Further, other characteristics of an individual may place him or her at greater risk for infection by particular types of organisms:

- Viruses cause the majority of pneumonias in young children (especially respiratory syncytial virus, parainfluenza and influenza viruses, and adenovirus).

- Adults are more frequently infected with bacteria (such as Streptococcus pneumoniae, Haemophilus influenzae, and Staphylococcus aureus).

- Pneumonia in older children and young adults is often caused by the bacteria-like Mycoplasma pneumoniae (the cause of what is often referred to as "walking" pneumonia).

- Pneumocystis carinii is an extremely important cause of pneumonia in patients with immune problems (such as patients being treated for cancer with chemotherapy, or patients with AIDS. Classically considered a parasite, it appears to be more related to fungi.

- People who have reason to come into contact with bird droppings, such as poultry workers, are at risk for pneumonia caused by the organism Chlamydia psittaci.

- A very large, serious outbreak of pneumonia occurred in 1976, when many people attending an American Legion convention were infected by a previously unknown organism. Subsequently named Legionella pneumophila, it causes what is now called "Legionnaire's disease." The organism was traced to air conditioning units in the convention's hotel.

Pneumonia is suspected in any patient who has fever, cough, chest pain, shortness of breath, and increased respirations (number of breaths per minute). Fever with a shaking chill is even more suspicious. Many patients cough up clumps of sputum, commonly known as spit. These secretions are produced in the alveoli during an infection or other inflammatory condition. They may appear streaked with pus or blood. Severe pneumonia results in the signs of oxygen deprivation. This includes blue appearance of the nail beds or lips (cyanosis).

The invading organism causes symptoms, in part, by provoking an overly-strong immune response in the lungs. In other words, the immune system, which should help fight off infections, kicks into such high gear, that it damages the lung tissue and makes it more susceptible to infection. The small blood vessels in the lungs (capillaries) become leaky, and protein-rich fluid seeps into the alveoli. This results in less functional area for oxygen-carbon dioxide exchange. The patient becomes relatively oxygen deprived, while retaining potentially damaging carbon dioxide. The patient breathes faster and faster, in an effort to bring in more oxygen and blow off more carbon dioxide.

Mucus production is increased, and the leaky capillaries may tinge the mucus with blood. Mucus plugs actually further decrease the efficiency of gas exchange in the lung. The alveoli fill further with fluid and debris from the large number of white blood cells being produced to fight the infection.

Consolidation, a feature of bacterial pneumonias, occurrs when the alveoli, which are normally hollow air spaces within the lung, instead become solid, due to quantities of fluid and debris.

Viral pneumonias and mycoplasma pneumonias do not result in consolidation. These types of pneumonia primarily infect the walls of the alveoli and the stroma of the lung.

Severe acute respiratory syndrome (sars)

Severe acute respiratory syndrome, or SARS, is a contagious and potentially fatal disease that first appeared in the form of a multi-country outbreak in early February 2003. Later that month, the CDC began to work with the World Health Organization (WHO) to investigate the cause(s) of SARS and to develop guidelines for infection control. SARS has been described as an "atypical pneumonia of unknown etiology;" by the end of March 2003, the disease agent was identified as a previously unknown coronavirus.

The early symptoms of SARS include a high fever with chills, headache, muscle cramps, and weakness. This early phase is followed by respiratory symptoms, usually a dry cough and painful or difficult breathing. Some patients require mechanical ventilation. The mortality rate of SARS is thought to be about 3%.

As of the end of March 2003, the CDC did not have clearly defined recommendations for treating SARS. Treatments that have been used include antibiotics known to be effective against bacterial pneumonia; ribavirin and other antiviral drugs; and steroids.

Diagnosis

For the most part, diagnosis is based on the patient's report of symptoms, combined with examination of the chest. Listening with a stethoscope will reveal abnormal sounds, and tapping on the patient's back (which should yield a resonant sound due to air filling the alveoli) may instead yield a dull thump if the alveoli are filled with fluid and debris.

Laboratory diagnosis can be made of some bacterial pneumonias by staining sputum with special chemicals and looking at it under a microscope. Identification of the specific type of bacteria may require culturing the sputum (using the sputum sample to grow greater numbers of the bacteria in a lab dish.).

X-ray examination of the chest may reveal certain abnormal changes associated with pneumonia. Localized shadows obscuring areas of the lung may indicate a bacterial pneumonia, while streaky or patchy appearing changes in the x-ray picture may indicate viral or mycoplasma pneumonia. These changes on x ray, however, are known to lag in time behind the patient's actual symptoms.

Treatment

Prior to the discovery of penicillin antibiotics, bacterial pneumonia was almost always fatal. Today, antibiotics, especially given early in the course of the disease, are very effective against bacterial causes of pneumonia. Erythromycin and tetracycline improve recovery time for symptoms of mycoplasma pneumonia. They, do not, however, eradicate the organisms. Amantadine and acyclovir may be helpful against certain viral pneumonias.

A newer antibiotic named linezolid (Zyvox) is being used to treat penicillin-resistant organisms that cause pneumonia. Linezolid is the first of a new line of antibiotics known as oxazolidinones. Another new drug known as ertapenem (Invanz) is reported to be effective in treating bacterial pneumonia.

Prognosis

Prognosis varies according to the type of organism causing the infection. Recovery following pneumonia with Mycoplasma pneumoniae is nearly 100%. Staphylococcus pneumoniae has a death rate of 30-40%. Similarly, infections with a number of gram negative bacteria (such as those in the gastrointestinal tract which can cause infection following aspiration) have a death rate of 25-50%. Streptococcus pneumoniae, the most common organism causing pneumonia, produces a death rate of about 5%. More complications occur in the very young or very old individuals who have multiple areas of the lung infected simultaneously. Individuals with other chronic illnesses (including cirrhosis of the liver, congestive heart failure, individuals without a functioning spleen, and individuals who have other diseases that result in a weakened immune system, experience complications. Patients with immune disorders, various types of cancer, transplant patients, and AIDS patients also experience complications.

Prevention

Because many bacterial pneumonias occur in patients who are first infected with the influenza virus (the flu), yearly vaccination against influenza can decrease the risk of pneumonia for certain patients. This is particularly true of the elderly and people with chronic diseases (such as asthma, cystic fibrosis, other lung or heart diseases, sickle cell disease, diabetes, kidney disease, and forms of cancer).

A specific vaccine against Streptococcus pneumoniae is very protective, and should also be administered to patients with chronic illnesses.

Patients who have decreased immune resistance are at higher risk for infection with Pneumocystis carinii. They are frequently put on a regular drug regimen of trimethoprim sulfa and/or inhaled pentamidine to avoid pneumocystis pneumonia.

Key terms

Alveoli — The little air sacs clustered at the ends of the bronchioles, in which oxygen-carbon dioxide exchange takes place.

Aspiration — A situation in which solids or liquids which should be swallowed into the stomach are instead breathed into the respiratory system.

Cilia — Hair-like projections from certain types of cells.

Consolidation — A condition in which lung tissue becomes firm and solid rather than elastic and air-filled because it has accumulated fluids and tissue debris.

Coronavirus — One of a family of RNA-containing viruses known to cause severe respiratory illnesses. In March 2003, a previously unknown coronavirus was identified as the causative agent of severe acute respiratory syndrome, or SARS.

Cyanosis — A bluish tinge to the skin that can occur when the blood oxygen level drops too low.

Sputum — Material produced within the alveoli in response to an infectious or inflammatory process.

Stroma — A term used to describe the supportive tissue surrounding a particular structure. An example is that tissue which surrounds and supports the actually functional lung tissue.

Resources

Books

Beers, Mark H., MD, and Robert Berkow, MD., editors. "Pneumonia." In The Merck Manual of Diagnosis and Therapy. Whitehouse Station, NJ: Merck Research Laboratories, 2004.

Periodicals

Arias, E., and B. L. Smith. "Deaths: Preliminary Data for 2001." National Vital Statistics Reports 51 (March 14, 2003): 1-44.

Birnbaum, Howard G., Melissa Morley, Paul E. Greenberg, et al. "Economic Burden of Pneumonia in an Employed Population." Archives of Internal Medicine 161 (December 10, 2001): 2725-2732.

Curran, M., D. Simpson, and C. Perry. "Ertapenem: A Review of Its Use in the Management of Bacterial Infections." Drugs 63 (2003): 1855-1878.

Lyseng-Williamson, K. A., and K. L. Goa. "Linezolid: In Infants and Children with Severe Gram-Positive Infections." Paediatric Drugs 5 (2003): 419-429.

"New Research Shows That Pneumonia, Septic Shock Run in Families." Genomics & Genetics Weekly November 16, 2001: 13.

"Outbreak of Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome—Worldwide, 2003." Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 52 (March 21, 2003): 226-228.

"Update: Outbreak of Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome—Worldwide, 2003." Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 52 (March 28, 2003): 241-246, 248.

Worcester, Sharon. "Ventilator-Linked Pneumonia." Internal Medicine News 34 (October 15, 2001): 32.

Wunderink, R. G., S. K. Cammarata, T. H. Oliphant, et al. "Continuation of a Randomized, Double-Blind, Multicenter Study of Linezolid Versus Vancomycin in the Treatment of Patients with Nosocomial Pneumonia." Clinical Therapeutics 25 (March 2003): 980-992.

Organizations

American Lung Association. 1740 Broadway, New York, NY 10019. (800) 586-4872. http://www.lungusa.org.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 1600 Clifton Rd., NE, Atlanta, GA 30333. (800) 311-3435, (404) 639-3311. http://www.cdc.gov.

Gale Encyclopedia of Medicine. Copyright 2008 The Gale Group, Inc. All rights reserved.

pneumonia

(noo-mon'ya, nu-) [ pneumono- + -ia], PNA

Inflammation of the lungs, usually due to infection with bacteria, viruses, or other pathogenic organisms. Clinically,

pneumonia indicates an infectious disease. Pulmonary inflammation due to other causes is called

pneumonitis. In the U.S., about 4,500,000 people contract pneumonia each year, and pneumonia is the sixth most common cause of death in the U.S. and the most common cause of death due to infectious disease. Pneumonia occurs most commonly in weakened people (those with cancer, heart or lung disease, immunosuppressive illnesses, diabetes mellitus, cirrhosis, malnutrition, and renal failure), but virulent pathogens can cause pneumonia in the healthy, as well. Smoking, general anesthesia, and endotracheal intubation increase the risk for developing pneumonia by inhibiting airway defenses and helping disease-causing germs reach the alveoli of the lungs. aspiration; pleural effusion; empyema; pleurisy; pneumonitis; tuberculosis (and names of lung pathogens);

Etiology

Pneumonias are categorized by site and cause. Lobar pneumonia affects most of a single lobe; bronchopneumonia involves smaller lung areas in several lobes; interstitial pneumonia affects tissues surrounding the alveoli and bronchi of the lung. Atypical pneumonias diffusely affect lung tissues rather than anatomical lobes or lobules. Community-acquired pneumonia is a lung infection that occurs in noninstitutionalized people, typically involving organisms such as viruses, Streptococcus pneumoniae, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Mycoplasma pneumoniae, Legionella pneumophila, Chlamydia pneumoniae, Moraxella species, or Pneumocystis carinii. Nosocomial pneumonia develops in patients in the hospital or nursing home; this type is most likely to be caused by gram-negative rods or staphylococcal species. Aspiration pneumonias result from the inhalation of oropharyngeal microorganisms and often involve anaerobic organisms. Pneumonias in immunocompromised patients sometimes are caused by Pneumocystis jiroveci or by fungal species such as Aspergillus. or Candida. Some fungal pneumonias occur in specific geographical regions of the U.S. For example, histoplasmosis is common in the Ohio River Valley, and coccidioidomycosis is found in the San Joaquin River Valley of southern California. Viral pneumonias may be caused by influenza, varicella-zoster, herpes, or adenoviruses.

Symptoms

Most patients with pneumonia have cough, shortness of breath, and fever although these symptoms are not universal. Bacterial pneumonias are marked by abrupt onset, with high fevers, shaking chills, pleuritic chest pain, and prostration. Patients with atypical pneumonias usually have lower temperatures and nonproductive coughs and appear less ill.

Prevention

Pneumococcal vaccine effectively prevents many forms of streptococcal pneumonia. This vaccine is recommended for people over 65; those with chronic respiratory, cardiac, or neuromuscular diseases; and patients with diabetes mellitus or renal failure.

Treatment

Treatment is based on the clinical presentation (such as community-acquired versus nosocomial), results of the Gram stain of sputum specimens, the radiographical appearance of the pneumonia, the degree of respiratory impairment, and the results of cultures. Many patients hospitalized with pneumonia require supplemental oxygen and analgesics. Initial antibiotic treatments for pneumonia should be given without delay and typically involve powerful, broad-spectrum drugs. The antibiotic used for subsequent therapy is guided by the results of cultured specimens taken on presentation.

Patient care

A large percentage of patients with pneumonia are not admitted to hospitals but are treated with antibiotics given on an outpatient basis. However, older adults, people with serious chronic diseases, and those with evidence of organ dysfunction, poor oxygenation, or acute decompensation may need hospitalization to reduce the risk of injury or death. Supportive care is provided to the patient to remove secretions and improve gas exchange. Such care includes position changes, deep breathing and coughing exercises, incentive spirometry, active and passive limb exercises, and assistance with self-care. Respiratory status is monitored by listening to the chest for crackles and/or wheezing, performing oximetry on a regular basis, and, when patients are failing, performing arterial blood gas studies. Supplemental oxygen is usually prescribed to maintain an oxygen saturation of > 92%. The patient is assessed for signs and symptoms of respiratory failure, sepsis, and shock. Mechanical ventilation is required in patients with respiratory failure. Analgesics are provided as prescribed to manage pain and discomfort and encourage good pulmonary toilet. A large percentage of patients receive care to remove secretions and to improve gas exchange. Such care includes position changes, deep-breathing, and coughing exercises. The patient is encouraged to verbalize concerns; diagnostic studies and therapeutic measures are explained, and the patient is taught about the importance of follow-up care. Outpatient therapy of community-acquired pneumonia can be recommended for selected patients who are young, otherwise healthy, and not hypoxic, hypotensive, hypothermic, or in renal failure. Activities are scheduled to allow for plenty of rest. The patient is taught hand hygiene and encouraged to wash hands with soap and water or use an alcohol-based hand wipe entirely over both hands after blowing the nose, coughing, using the bathroom, or eating or drinking. Only disposable tissues are used for sneezing and coughing. Used tissues are deposited in a lined bag taped to the bedside and are disposed of frequently according to agency policy. Unless otherwise restricted, the patient should drink eight 12-ounce glasses of water daily to help thin and loosen mucous secretions. Each patient’s meal preferences and restrictions are discussed to plan a diet that ensures adequate high-caloric intake. Emotional support is provided, and all procedures and treatments are explained. The patient who smokes is taught the relationship between smoking and lung diseases (including the increased risk of respiratory infections) and referred for support group assistance with quitting as needed. Pneumonia prevention is aided by encouraging individuals to avoid indiscriminate antibiotic use, receive pneumonia and influenza vaccinations, perform deep-breathing and coughing exercises when confined to bed and after surgery, and ambulate early after surgery. Aspiration pneumonia is prevented in tube-fed patients by correct positioning and slow, low-volume feedings. The chronically ill and debilitated in nursing homes should have swallowing function assessed as necessary; caregivers should be taught correct feeding techniques to prevent aspiration.

abortive pneumonia

An obsolete term for mild pneumonia with a brief course.

acute lobar pneumonia

Lobar pneumonia.pneumonia alba

A pneumonia seen in stillborn infants; caused by congenital syphilis.

artificial airway-associated pneumonia

Ventilator-associated pneumonia.aspiration pneumonia

Pneumonia caused by inhalation of gastric contents, food, or other substances. A frequent cause is loss of the gag reflex in patients with central nervous system depression or damage or alcoholic intoxication with stupor and vomiting. This condition also occurs in newborns who inhale infected amniotic fluid, meconium, or vaginal secretions during delivery.

atypical pneumonia

Pneumonia caused by a virus or Mycoplasma pneumoniae. The symptoms are low-grade fever, nonproductive cough, pharyngitis, myalgia, and minimal adventitious lung sounds.

bacterial pneumonia

Pneumonia caused by bacteria such as streptococcus, Staphylococcus aureus, Klebsiella, or coliforms.

chlamydial pneumonia

An atypical pneumonia caused by Chlamydia species, characterized clinically by cough, low-grade fever, sore throat, and malaise. A chest x-ray taken during the illness is more likely to show diffuse lung involvement than a lobar pneumonia.

community-acquired pneumonia

Pneumonia occurring in outpatients, often caused by infection with streptococcus, Haemophilus influenzae, Staphylococcus aureus, and atypical organisms such as Legionella species. Mortality is approximately 15% but depends on many host and pathogen features.

desquamative interstitial pneumonia

Pneumonia of unknown cause, accompanied by cellular infiltration or fibrosis in the pulmonary interstitium. Progressive dyspnea and a nonproductive cough are symptoms characterizing this disease. Clubbing of the fingers is a common finding. Diffusion of oxygen and carbon dioxide is abnormal. Diagnosis is made by lung biopsy. The condition is treated by corticosteroids.

double pneumonia

Pneumonia that involves both lungs or two lobes.

embolic pneumonia

Pneumonia following embolization of a pulmonary blood vessel.

eosinophilic pneumonia

Infiltration of the lung by eosinophils, typically found in patients with peripheral eosinophilia. The cause is usually unknown; occasionally, the condition responds to the administration of corticosteroids. In some cases, a specific underlying cause is found, such as the recent initiation of cigarette smoking or an allergic drug reaction. Infection with some parasites or fungi also can trigger the disease.

Synonym: pulmonary infiltration with eosinophilia; fibrous pneumonia

Pneumonia followed by formation of scar tissue.

Friedländer pneumonia

See: Friedländer pneumoniagangrenous pneumonia

Pulmonary gangrene.

giant cell pneumonia

An interstitial pneumonitis of infancy and childhood. The lung tissue contains multinucleated giant cells. The disease often occurs in connection with measles.

healthcare-associated pneumonia

Nosocomial pneumonia.hypostatic pneumonia

Pneumonia occurring in elderly or bed-ridden patients who remain constantly in the same position. Ventilation is greatest in dependent areas. Remaining in one position causes hypoventilation in many areas, causing alveolar collapse (atelectasis) and creating a pulmonary environment that supports the growth of bacteria or other organisms. Development of this condition is prevented by having the patient change positions and take deep breaths to inflate peripheral alveoli.

Patient care

Prevention is the most important factor, esp. in older and immobile persons. Patients should be moved and turned frequently at least every 1 to 2 hr. The nurse and respiratory therapist should monitor respiratory status by frequently auscultating for crackles, gurgles, and wheezes and encourage the patient to engage in active movement and to perform deep-breathing and coughing exercises frequently and regularly. Incentive spirometry may prove useful in patients who need added encouragement to deep breathe periodically.

intrauterine pneumonia

Pneumonia contracted in utero.

Legionella pneumonia

Legionnaires' disease.lipoid pneumonia

Damage to lung tissue that results from aspiration of oils. It may occur repeatedly in patients with impaired swallowing mechanisms or in persons affected by esophageal disorders, such as esophageal carcinoma, achalasia, or scleroderma. Mineral oils and cooking oils often are responsible. Most cases resolve spontaneously, but corticosteroids sometimes are used as treatment to reduce inflammatory changes. Distinguishing lipoid pneumonia from bacterial pneumonia may require endoscopy.

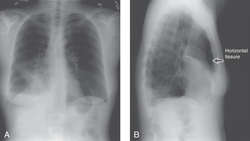

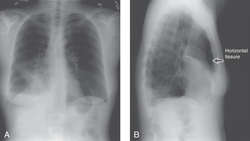

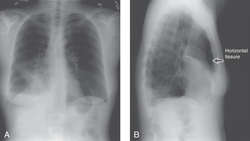

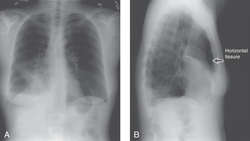

LOBAR PNEUMONIA: (A) The right heart border is obscured by the infection, (B) Lateral view shows dense (white) infiltrate sharply defined by horizontal fissure (Courtesy of Harvey Hatch, MD, Curry General Hospital)

LOBAR PNEUMONIA

lobar pneumonia

Pneumonia infecting one or more lobes of the lung, usually caused by Streptococcus pneumoniae. The pathologic changes are, in order, congestion; redness and firmness due to exudate and red blood cells in the alveoli; and, finally, gray hepatization as the exudate degenerates and is absorbed. Synonym: acute lobar pneumonia See: illustration

illustrationneonatal pneumonia

Lung infection occurring in the first few days of life due to uterine exposure to infectious microorganisms or to infection during or immediately after birth. Common causes include viruses (such as herpes simplex) and bacteria (such as group B streptococcus, Chlamydia, Escherichia coli, Listeria).

nosocomial pneumonia

Pneumonia occurring after 48 hours of confinement in a hospital, intensive care unit, or nursing home. It is often the result of infection with gram-negative pathogens or multiply drug-resistant bacteria and includes both ventilator-associated pneumonias and other lower respiratory tract infections. Synonym: healthcare-associated pneumonia

pneumococcal pneumonia

The most common form of pneumonia in the U.S., affecting about half a million people each year. It often begins with hard-shaking chills and may be fatal, esp. in the elderly or those with underlying diseases. It usually strikes smokers, people with underlying lung diseases, those recently infected with influenza or those with sickle-cell anemia, chronic or heavy alcohol use, or cirrhosis.

Symptoms

Fevers, body-shaking chills, productive cough, pleurisy, prostration, and sweating.

Treatment

Penicillin may be used when the pneumococcus is sensitive to this agent, but the incidence of penicillin resistance in pneumococci is rapidly growing. Third-generation cephalosporins, erythromycin, vancomycin, and linezolid, are alternative agents.

Patient care

Vaccination provides passive immunity against many serotypes of pneumococcal pneumonia. People over the age of 65 or those with heart, lung, liver, kidney, or immunosuppressive diseases should be immunized as should infants under the age of two.

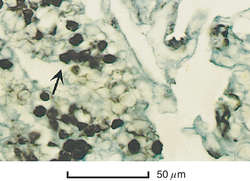

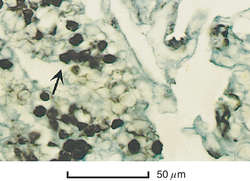

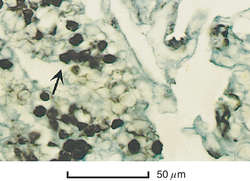

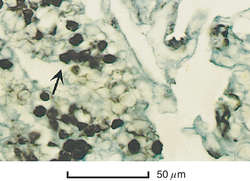

PNEUMOCYSTIS CARINII PNEUMONIA: Silver-stained cysts in lung tissue (×400)

PNEUMOCYSTIS CARINII PNEUMONIA

Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia

Abbreviation: PCP

A subacute opportunistic infection marked by fever, nonproductive cough, tachypnea, dyspnea, and hypoxemia. It is caused by

Pneumocystis carinii, the former name of

Pneumocystis jiroveci, an organism formerly thought to be a protozoan but now generally accepted as a fungus. The disease is seen principally in immunosuppressed patients, such as those with AIDS or who have received an organ transplant and immunosuppressant drugs. Without treatment, the progressive respiratory failure that the infection causes is ultimately fatal.

Diagnosis

The disease should be suspected in patients with human immunodeficiency virus infection or other risk factors for the disease who present with cough and shortness of breath. Chest x-ray examination may reveal diffuse interstitial infiltrates, upper lobe disease, spontaneous pneumothorax, or cystic lung disease. The diagnosis is confirmed with special stains of sputum, bronchial washings, or lung biopsy specimens. See: illustration

Treatment

Oral trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole effectively protects against PCP, and is also the drug of choice for active infection. Other drugs that are active against PCP include pentamidine, trimethoprim in combination with dapsone, and atovaquone. Corticosteroids are used as adjunctive therapy when treating markedly hypoxic patients, e.g., those who present with an alveolar-arterial oxygen gradient of more than 35 mm Hg. The introduction of highly active antiretroviral drug cocktails for AIDS patients has markedly reduced the incidence of PCP.

secondary pneumonia

Pneumonia that occurs in connection with a specific systemic disease such as typhoid, diphtheria, or plague.

tuberculous pneumonia

Pneumonia caused by Mycobacterium tuberculosis. See: tuberculosis

tularemic pneumonia

Pneumonia caused by Francisella tularensis. It may be primary or associated with tularemia.

ventilator-associated pneumonia

In patients receiving invasive mechanical ventilation, a new and persistent infiltrate seen on chest x-ray associated with fever, elevated or depressed white blood cell counts, and sputum that is either purulent or full of disease-causing bacteria. Synonym: artificial airway-associated pneumonia

viral pneumonia

Any infections of the lower respiratory tract (the lungs, bronchioles, and trachea) caused by viral species such as adenovirus, coronavirus, herpesviruses, influenza viruses, and respiratory syncytial viruses. Viral pneumonias may range from mild respiratory infections (with nonproductive cough and low-grade fevers) to life-threatening and highly contagious illnesses (such as SARS). See: bronchitis; bronchiolitis

Medical Dictionary, © 2009 Farlex and Partners