Medical term:

d

disease

[dĭ-zēz´]dis·ease

(di-zēz'),See also: syndrome. Synonym(s): illness, morbus, sickness

See also: syndrome.

dis·ease

disease

(dĭ-zēz′)disease

Alternative medicineA state of disharmonious vibration of the elements and forces affecting humans on one or more planes of existence.

Cause of disease (alternative medicine)

• Accumulation of toxic material (e.g., through poor diet).

• Incorrect or unbalanced diet.

• Improper posture.

• Destructive emotions.

• The use of suppressive drugs and vaccines.

• Use of alcohol, coffee and tobacco.

• Environmental hazards in the form of air and water pollution.

• Occupational hazards (e.g., chemicals, poor air quality, noise pollution, asbestos and others).

• Inherited factors and predispositions.

• Infections.

Drug slang

A regional term for drug of choice.

Medspeak

(1) A condition in which bodily function is interfered with or damaged, resulting in characteristic signs and symptoms.

(2) The loss of a state of wellness due to either a failure in physiologic adaptation mechanisms or an overwhelming of the natural defences by a noxious agent or pathogen.

disease

Medtalkdis·ease

(di-zēz)Synonym(s): illness, morbus, sickness.

See also: syndrome

disease

disease

an abnormality of an animal or plant caused by a pathogenic organism or the deficiency of a vital nutrient that affects performance of the vital functions and usually gives diagnostic symptoms.disease

autoimmune disease A disease produced when the immune response of an individual is directed against its own cells or tissues. It is not yet known exactly what causes the body to react to one's own antigens as if they were foreign. Examples: diabetes mellitus type 1; Graves' disease; multiple sclerosis; myasthenia gravis; rheumatoid arthritis; Reiter's disease; Sjögren's syndrome.

Batten-Mayou disease Juvenile form of amaurotic family idiocy. It is characterized by progressive degeneration of the retina, which eventually leads to blindness. Syn. Spielmeyer-Stock disease.

Behçet's disease See Behçet's syndrome.

Benson's disease See asteroid hyalosis.

Berlin's disease A traumatic phenomenon in which the posterior pole of the retina develops oedema (and haemorrhages). Syn. commotio retinae.

Best's disease An autosomal dominant inherited degeneration in which there is an accumulation of lipofuscin within the retinal pigment epithelium, which interferes with its function. It is caused by a mutation in bestrophin gene (BEST1). The disease is characterized by the appearance on the retina in the first and second decades of life of a bright orange deposit, resembling the yolk of an egg (vitelliform), with practically no effect on vision. It eventually absorbs, leaving scarring, pigmentary changes and impairment of central vision in most cases, although in some cases the retinal lesion may be eccentric, with very little effect on vision. The electrooculogram is abnormal throughout the development of the disease from pre-vitelliform, vitelliform and the end-stage when there is scarring or atrophy. Syn. Best's macular dystrophy; juvenile vitelliform macular dystrophy; vitelliform macular dystrophy. Mutation in the VMD2 gene can cause adult vitelliform macular dystrophy, a condition characterized by smaller macular lesions and very little impairment of vision. See pattern dystrophy.

Bowen's disease A disease characterized by a slow-growing tumour of the epidermis of the skin which may involve the corneal or conjunctival epithelium.

Coats' disease Chronic, progressive retinal vascular anomalies, usually unilateral, occurring predominantly in young males. It is characterized by retinal exudates, irregular dilatation (telangiectasia) and tortuosity of retinal vessels and appears as a whitish fundus reflex (leukocoria). Subretinal haemorrhages are frequent and eventually retinal detachment may occur. The main symptom is a decrease in central or peripheral vision, although it may be asymptomatic in some patients. Management may involve photocoagulation or cryotherapy. A less severe form of the disease is called Leber's miliary aneurysms. Syn. retinal telangiectasia.

Crohn's disease A type of inflammatory, chronic bowel disease characterized by granulomatous inflammation of the bowel wall causing fever, diarrhoea, abdominal pain and weight loss. The ocular manifestations include acute iridocyclitis, scleritis, conjunctivitis and corneal infiltrates.

Devic's disease A demyelinative disease of the optic nerve, the optic chiasma and the spinal cord characterized by a bilateral acute optic neuritis with a transverse inflammation of the spinal cord. Loss of visual acuity occurs very rapidly and is accompanied by ascending paralysis. There is no treatment for this disease. Syn. neuromyelitis optica.

Eales' disease A non-specific peripheral retinal periphlebitis (i.e. an inflammation of the outer coat of a vein) that usually affects mostly young males, often those who have active or healed tuberculosis. It is characterized by recurrent haemorrhages in the retina and vitreous. This disease is a prime example of retinal vasculitis.

Fabry's disease An X-linked recessive disease caused by mutations in the gene encoding alpha-galactosidase A (GLA) and characterized by an abnormal accumulation of glycolipid in the tissues. It appears as small purple skin lesions on the trunk and there may be renal and cardiovascular abnormalities. Ocular signs include whorl-like corneal opacities, star-shaped lens opacities, and tortuous conjunctival and retinal blood vessels.

Graves' disease An autoimmune disorder in which immunoglobulin antibodies bind to thyroid-stimulating hormone receptors in the thyroid gland and stimulate secretion of thyroid hormones leading to hyperthyroidism. The main ocular manifestations (called Graves' ophthalmopathy) are exophthalmos, retraction of the eyelids (Dalrymple's sign), conjunctival hyperaemia, lid lag in which the upper lid follows after a latent period when the eye looks downward (von Graefe's sign), defective eye movements (restrictive myopathy) and optic neuropathy, besides increased pulse rate, tremors, loss of weight and diarrhoea. It typically affects women between the ages of 20 and 50 years. Most common signs associated with the disease are those of von Graefe and Moebius. Syn. thyrotoxicosis. If only the eye signs of the disease are present without clinical evidence of hyperthyroidism, the disease is called euthyroid or ophthalmic Graves' disease. Treatment begins with control of the hyperthyroidism (if present). Some cases may recover spontaneously with time. Mild cases of ocular deviations and restrictions may benefit from a prismatic correction. Corticosteroids and radiotherapy may be needed and surgery is a common form of management, especially when there is diplopia in the primary position of gaze. See accommodative infacility; exophthalmos; thyroid ophthalmopathy.

Harada's disease A disease characterized by bilateral exudative uveitis associated with alopecia, vitiligo and hearing defects. However, as many aspects of this entity overlap clinically and histopathologically with the Vogt-Koyanagi syndrome it is nowadays combined and called the Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada syndrome.

von Hippel's disease A rare disease, sometimes familial, in which haemangiomata occur in the retina where they appear ophthalmoscopically as one or more round, elevated reddish nodules. The condition is progressive and takes years before there is a complete loss of vision. Syn. angiomatosis retinae.

von Hippel-Lindau disease Retinal haemangioblastoma involving one or both eyes associated with similar tumours in the cerebellum and spinal cord and sometimes cysts of the kidney and pancreas. Ophthalmoscopic examination shows a reddish, slightly elevated tumour.

Leber's disease See Leber's hereditary optic atrophy.

Niemann-Pick disease An autosomal recessive inherited lipid storage disorder characterized by a partial destruction of the retinal ganglion cells and a demyelination of many parts of the nervous system. It is caused by mutation in the NPC1 gene. The condition usually involves children of Jewish parentage. When the retina is involved, there is a reddish central area (cherry-red spot) surrounded by a white oedematous area. The disease usually leads to death by the age of two. This disease is differentiated from Tay-Sachs disease because of its widespread involvement and gross enlargement of the liver and the spleen. Syn. sphingomyelin lipidosis. See Tay-Sachs disease.

Norrie's disease An inherited X-linked recessive disorder characterized by bilateral congenital blindness. It is caused by mutation in the norrin gene (NDP). The initial ocular presentation is leukocoria. It then progresses to cataract, corneal opacification and phthisis bulbi. The condition may be associated with mental retardation and hearing defects. Syn. oculoacoustico-cerebral degeneration; Andersen-Warburg syndrome.

Oguchi's disease An autosomal recessive, inherited night blindness occurring mainly in Japan. All other visual capabilities are usually unimpaired but the patient presents an abnormal golden brown fundus reflex in the light-adapted state, which becomes a normal colour with dark-adaptation (Mizuo phenomenon). It is presumed to be due to an abnormality in the neural network of the retina. The disease can be caused by mutation in the arrestin gene (SAG) or the rhodopsin kinase gene (GRK1).ophthalmic Graves' d. See Graves' disease.

Paget's disease Hereditary systemic disorder of the skeletal system accompanied by visual disturbances, the most common being retinal arteriosclerosis. See angioid streaks; arteriosclerosis.

von Recklinghausen's disease An autosomal dominant inherited disease with a gene locus at 17q11. It is caused by mutation in the neurofibromin gene. It is characterized by tumours in the central nervous system and in cranial nerves, enlarged head, 'café au lait' spots on the skin, choroidal naevi, optic nerve glioma, peripheral neurofibromas (e.g. on the eyelid) and Lisch nodules. Glaucoma may occur. Syn. neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF-1).

Refsum's disease See Refsum's syndrome.

Reiter's disease A systemic syndrome characterized by a triad of three diseases: urethritis, arthritis and conjunctivitis. Keratitis and iridocyclitis may follow as complications. It occurs mainly in young men typically following urethritis and less commonly after an attack of dysentery or acute arthritis, which usually affects the knees, ankles and Achilles tendon. Syn. Reiter's syndrome.

Sandhoff's disease An autosomal recessive inherited disease similar to Tay-Sachs disease with the same signs, but differing in that both the enzymes hexosaminidase A and B are defective and it develops more rapidly and can be found among the general population. The main ocular manifestation is a whitish area in the central retina with a cherry-red spot which eventually fades and the optic disc develops atrophy. Syn. Gm2 gangliosidosis type2.

sickle-cell disease A hereditary anaemia encountered among black and dark-skinned people due to a defect in the haemoglobin. It is characterized by retinal neovascularization, haemorrhages and exudates, cataract and subconjunctival haemorrhage. Syn. sickle-cell anaemia.

Spielmeyer-Stock disease See Batten-Mayou disease.

Stargardt's disease An autosomal recessive inherited disorder of the retina occurring in the first or second decade of life and affecting the central region of the retina. A few cases are inherited as an autosomal dominant trait. Known causes of the disease include a mutation in one of the following genes: ABCA4, CNGB3 and ELOVL4. There is an accumulation of lipofuscin within the retinal pigment epithelium, which interferes with its function. With time a lesion develops at the macula, which has a 'beaten-bronze' reflex. It is often surrounded by yellow-white flecks. There is a loss of central vision but peripheral vision is usually normal. Myopia is very common. Management usually consists of a high plus correction for near to magnify the retinal image and wearing UV-protecting sunglasses. Syn. Stargardt's macular dystrophy. See macular dysrophy; fundus flavi-maculatus.

Steinert's disease See myotonic dystrophy.

Still's disease See juvenile rheumatoid arthritis.

Sturge-Weber disease See Sturge-Weber syndrome.

Tay-Sachs disease An autosomal recessive lipid storage disorder caused by a deficiency of the enzyme hexosaminidase A which leads to an accumulation of Gm2 ganglioside (a fatty acid derivative) in the ganglion cells of both the retina and the brain. It has its onset in the first year of life, vision is affected and the central retina shows a whitish area with a reddish central area (cherry-red spot), which fades and the optic disc develops atrophy. Eventually the eye becomes blind and death occurs, usually at about the age of 30 months. It affects Jewish infants more than others by a factor of about ten to one. Syn. Gm2 gangliosidosis type 1; infantile amaurotic familial idiocy. See Niemann-Pick disease.

Terrien's disease See corneal ectasia.

Wagner's disease See Wagner's syndrome.

Wernicke's disease A disease characterized by disturbances in ocular motility, pupillary reactions, nystagmus and ataxia. It is mainly due to thiamin deficiency and is frequently encountered in chronic alcoholics. Syn. Wernicke's syndrome.

Wilson's disease A systemic disease resulting from a deficiency of the alpha-2-globulin ceruloplasmin beginning in the first or second decade of life. It is characterized by widespread deposition of copper in the tissues, tremor, muscular rigidity, irregular involuntary movements, emotional instability and hepatic disorders. The ocular features are degenerative changes in the lenticular nucleus and most noticeably a Kayser-Fleischer ring. Syn. hepatolenticular degeneration; lenticular progressive degeneration; pseudosclerosis of Westphal.

dis·ease

(di-zēz)Patient discussion about disease

Q. My sister has this disease and she works at a daycare.Can this disease be airbourne? Children come to the daycare sick. Some of her co-workers were out from work because they got sick from some of the children.

Q. Mood- disorder? What will happen to the people who refuse treatment? I know someone whose mother got diagnosed with "mood- disorder" and now this person says that she don't have it. But all her brothers and sisters have this, and are on medication. Is there a way to save our family heritage?

Q. Whats schizoaffective disease its a mental disease

diabetes

[di″ah-be´tēz]Treatment of pituitary diabetes insipidus consists of administration of vasopressin. A synthetic analogue of vasopressin (DDAVP) can be administered as a nasal spray, providing antidiuretic activity for 8 to 20 hours, and is currently the drug of choice. Patient care includes instruction in self-administration of the drug, its expected action, symptoms that indicate a need to adjust the dosage, and the importance of follow-up visits. Patients with this condition should wear some form of medical identification at all times.

The American Diabetes Association sponsored an international panel in 1995 to review the literature and recommend updates of the classification of diabetes mellitus. The definitions and descriptions that follow are drawn from the Report of the Expert Committee on the Diagnosis and Classification of Diabetes Mellitus. The report was first approved in 1997 and modified in 1999. Although other terms are found in older literature and remain in use, their use in current clinical practice is inappropriate. Epidemiologic and research studies are facilitated by use of a common language.

The Expert Committee notes that most cases of diabetes fall into two broad categories, which are called Type 1 and Type 2. There are also other specific types, such as gestational diabetes and impaired glucose homeostasis. See table for definitions of types of diabetes mellitus.

The typical symptoms of diabetes mellitus are the three “polys:” polyuria, polydipsia, and polyphagia. Because of insulin deficiency, the assimilation and storage of glucose in muscle adipose tissues, and the liver is greatly diminished. This produces an accumulation of glucose in the blood and creates an increase in its osmolarity. In response to this increased osmotic pressure there is depletion of intracellular water and osmotic diuresis. The water loss creates intense thirst and increased urination. The increased appetite (polyphagia) is not as clearly understood. It may be the result of the body's effort to increase its supply of energy foods even though eating more carbohydrates in the absence of sufficient insulin does not meet the energy needs of the cells.

Fatigue and muscle weakness occur because the glucose needed for energy simply is not metabolized properly. Weight loss in type 1 diabetes patients occurs partly because of the loss of body fluid and partly because in the absence of sufficient insulin the body begins to metabolize its own proteins and stored fat. The oxidation of fats is incomplete, however, and the fatty acids are converted into ketone bodies. When the kidney is no longer able to handle the excess ketones the patient develops ketosis. The overwhelming presence of the strong organic acids in the blood lowers the pH and leads to severe and potentially fatal ketoacidosis.

The metabolism of body protein when sufficient amounts of insulin are not available causes an elevated blood urea nitrogen. This first occurs because the nitrogen component of protein is discarded in the blood when the body metabolizes its own proteins to obtain the glucose it needs.

Persons with diabetes are prone to infection, delayed healing, and vascular disease. The ease with which poorly controlled diabetic persons develop an infection is thought to be due in part to decreased chemotaxis of leukocytes, abnormal phagocyte function, and diminished blood supply because of atherosclerotic changes in the blood vessels. An impaired blood supply means a deficit in the protective defensive cells transported in the blood. Excessive glucose allows organisms to grow out of control.

Another manifestation of diabetes mellitus is visual disturbance due to increased osmolarity of the blood and accumulation of fluid in the eyeball, which changes its shape. Once the diabetes is under control, visual problems should abate. Persistent vaginitis and urinary tract infection also may be symptoms of diabetes in females.

Visual impairment and blindness are common sequelae of uncontrolled diabetes. The three most frequently occurring problems involving the eye are diabetic retinopathy, cataracts, and glaucoma. photocoagulation of destructive lesions of the retina with laser beams can be used to delay further progress of pathologic changes and thereby preserve sight in the affected eye.

Another area of pathologic changes associated with diabetes mellitus is the nervous system (diabetic neuropathy), particularly in the peripheral nerves of the lower extremities. The patient typically experiences a “stocking-type” anesthesia beginning about 10 years after the onset of the disease. There may eventually be almost total anesthesia of the affected part with the potential for serious injury to the part without the patient being aware of it. In contrast, some patients experience debilitating pain and hyperesthesia, with loss of deep tendon reflexes.

Other problems related to the destruction of nerve tissue are the result of autonomic nervous system involvement. These include impotence, orthostatic hypotension, delayed gastric emptying, diarrhea or constipation, and asymptomatic retention of urine in the bladder.

Although age of onset and length of the disease process are related to the frequency with which vascular, renal, and neurologic complications develop, there are some patients who remain relatively free of sequelae even into the later years of their lives. Because diabetes mellitus is not a single disease but rather a complex constellation of syndromes, each patient has a unique response to the disease process.

The protocol for therapy is determined by the type of diabetes; patients with either type 1 or type 2 must pay attention to their diet and exercise regimens. Insulin therapy may be prescribed for patients with type 2 diabetes as well as any who are dependent on insulin. In most cases, the type 2 diabetes patient can be treated effectively by reducing caloric intake, maintaining target weight, and promoting physical exercise.

Diet. In general, the diabetic diet is geared toward providing adequate nutrition with sufficient calories to maintain normal body weight; the intake of food is adjusted so that blood sugar and serum cholesterol levels are kept within acceptable limits. Overweight diabetic patients should limit caloric intake until target weight is achieved. In persons with type 2 diabetes this usually results in marked improvement and may eliminate the need for drugs such as oral hypoglycemic agents.

The patient, physician, nurse, and dietician must carefully evaluate the patient's life style, nutritional needs, and ability to comply with the proposed dietary prescription. There are a variety of meal planning systems that can be used by the patient with diabetes; each has benefits and drawbacks that need to be evaluated in order to maximize compliance. Two of the most frequently used ones are the exchange system (see accompanying table) and the carbohydrate counting system.

In the exchange system, foods are divided into six food groups (starch, meat, vegetable, fruit, milk, and fat) and the patient is taught to select items from each food group as ordered. Items in each group may be exchanged for each other in specified portions. The patient should avoid concentrated sweets and should increase fiber in the diet. Special dietetic foods are not necessary. Patient teaching should emphasize that a diabetic diet is a healthy diet that all members of the family can follow.

The carbohydrate counting system focuses on matching the unit of insulin to the total number of grams of carbohydrate in food eaten. This system is the most accurate method for calculating insulin to food intake.

It is especially important that persons with diabetes who are taking insulin not skip meals; they must also be sure to eat the prescribed amounts at the prescribed times during the day. Since the insulin-dependent diabetic needs to match food consumption to the available insulin, it is advantageous to increase the number of daily feedings by adding snacks between meals and at bedtime.

Exercise. A program of regular exercise gives anyone a sense of good health and well-being; for persons with diabetes it gives added benefits by helping to control blood glucose levels, promoting circulation to peripheral tissues, and strengthening the heart beat. In addition, there is evidence that exercise increases the number of insulin receptor sites on the surface of cells and thus facilitates the metabolism of glucose. Many specialists in diabetes consider exercise so important in the management of diabetes that they prescribe rather than suggest exercise.

Persons with diabetes who take insulin must be careful about indulging in unplanned exercise. Strenuous physical activity can rapidly lower their blood sugar and precipitate a hypoglycemic reaction. For a person whose blood glucose level is over 250 mg/dl, the advice would be not to exercise at all. At this range, the levels of insulin are too low and the body would have difficulty transporting glucose into exercising muscles. The result of exercise would be a rise in blood glucose levels.

Insulin Therapy. Exogenous insulin is given to patients with diabetes mellitus as a supplement to the insufficient amount of endogenous insulin that they produce. In some cases, this must make up for an absolute lack of insulin from the pancreas. Exogenous insulin is available in various types. It must be given by injection, usually subcutaneously, and because it is a potent drug, the dosage must be measured meticulously. Commonly, regular insulin, which is a fast-acting insulin with a short span of action, is mixed with one of the longer-acting insulins and both types are administered in one injection.

Human insulin (Humulin) is produced by recombinant DNA technology. This highly purified biosynthetic insulin reduces the incidence of allergic reactions and the changes in subcutaneous tissues (lipodystrophy) at sites of injection.

Recently, battery-operated insulin pumps have been developed that can be programmed to mimic normal insulin secretion more closely. A person wearing an insulin pump still must monitor blood sugar several times a day and adjust the dosage, and not all diabetic patients are motivated or suited to such vigilance. It is hoped that in the future an implantable or external pump system may be perfected, containing a glucose sensor. In response to data from the sensor the pump will automatically deliver insulin according to changing levels of blood glucose.

Oral Agents. Oral antidiabetic drugs (see hypoglycemic agents) are sometimes prescribed for patients with type 2 diabetes who cannot control their blood glucose with diet and exercise. These are not oral forms of insulin; they are sulfonylureas, chemically related to the sulfonamide antibiotics. Patients receiving them should be taught that the drug they are taking does not eliminate the need for a diet and exercise program. Only the prescribed dosage should be taken; it should never be increased to make up for dietary indiscretions or discontinued unless authorized by the physician.

1. Monitoring of blood glucose status. In the past, urine testing was an integral part of the management of diabetes, but it has largely been replaced in recent years by self monitoring of blood glucose. Reasons for this are that blood testing is more accurate, glucose in the urine shows up only after the blood sugar level is high, and individual renal thresholds vary greatly and can change when certain medications are taken. As a person grows older and the kidney is less able to eliminate sugar in the urine, the renal threshold rises and less sugar is spilled into the urine. The position statement of the American Diabetes Association on Tests of Glycemia in Diabetes notes that urine testing still plays a role in monitoring in type 1 and gestational diabetes, and in pregnancy with pre-existing diabetes, as a way to test for ketones. All people with diabetes should test for ketones during times of acute illness or stress and when blood glucose levels are consistently elevated.

2. Home glucose monitoring using either a visually read test or a digital readout of the glucose concentration in a drop of blood. Patients can usually learn to use the necessary equipment and perform finger sticks. They keep a daily record of findings and are taught to adjust insulin dosage accordingly. More recent glucose monitoring devices can draw blood from other locations on the body, such as the forearm.

3. Pathophysiology of diabetes mellitus, including functions of the pancreas and the long-term effects of uncontrolled diabetes.

4. Insulin administration (if appropriate), including types of insulin and syringes, rotation of sites of injection, injection techniques, and pump therapy instructions.

5. Signs and symptoms ofhyperglycemiaandhypoglycemia, and measures to take when they occur. (See accompanying table.) It is important for patients to become familiar with specific signs that are unique to themselves. Each person responds differently and may exhibit symptoms different from those experienced by others. It should be noted that the signs and symptoms may vary even within one individual. Thus it is vital that the person understand all reactions that could occur. When there is doubt, a simple blood glucose reading will determine the actions that should be taken.

6. Oral antidiabetic agents, including information about drug-drug interactions, proper administration, and potential side effects.

7. Personal hygiene and activities of daily living, including general skin care, foot care, treatment of minor injuries to avoid infection, a formal exercise program as well as exercise at school or at work, recreational activity, and travel.

8. Identification tag and card and needed medical information.

9. Information on what to do on “sick days” when nausea, vomiting, or respiratory infection can interfere with the usual meals and exercise.

10. Importance of keeping appointments and staying in touch with a health care provider for consultation and assessment. Periodic evaluation of the binding of glucose to hemoglobin (glycosylated hemoglobin or hemoglobin A1C testing) can give information about the effectiveness of the prescribed regimen and whether any changes need to be made. The ADA position statement on tests of glycemia in diabetes recommends routine testing for all patients with diabetes. It should be a part of the initial assessment of the patient, with subsequent measurements every three months to determine if the patient's metabolic control has been reached and maintained.

di·a·be·tes

(dī'ă-bē'tēz), Avoid using the simple word diabetes for diabetes mellitus unless the sense is clear from the context.diabetes

(dī′ə-bē′tĭs, -tēz)diabetes

See Diabetes insipidus, Diabetes mellitus.di·a·be·tes

(dī-ă-bē'tēz)diabetes

(di?a-bet'ez) [Gr. diabetes, (one) passing through]brittle diabetes

Etiology

Diabetes may be brittle when insulin is not well absorbed; insulin requirements vary rapidly; insulin is improperly prepared or administered; the Somogyi phenomenon is present; the patient has coexisting anorexia or bulimia; the patient's daily exercise routine, diet, or medication schedule varies; or physiological or psychological stress is persistent.

brittle diabetes mellitus

Brittle diabetes.bronze diabetes

Hemochromatosis.chemical diabetes

cystic-fibrosis-related diabetes

Abbreviation: CFRDPatient Care

Although CFRD can be diagnosed with fasting glucose blood tests or hemoglobin A1c levels, many experts recommend using an oral glucose tolerance test. Fifteen to thirty percent of patients with CF are affected by their 20th birthday, and perhaps as many as half have the disease by age 30. CFRD is associated with more severe lung disease than is experienced by patients with CF and normal glucose tolerance. Oral hypoglycemic agents, insulin, and exercise are the primary methods of treatment. Caloric restriction, a cornerstone of treatment for other forms of diabetes, is relatively contraindicated because of the need for aggressive nutritional supplementation in CF patients.

double diabetes

endocrine diabetes

fibrocalculous pancreatic diabetes

gestational diabetes

Abbreviation: GDMGDM affects a large percentage of pregnant American women, ranging from about 1.5 to 14 %, depending on the ethnic group studied. Although gestational diabetes usually subsides after delivery, women with GDM have a 45% risk of recurrence with the next pregnancy and a significant risk of developing type 2 diabetes later in life.

Diagnosis

Although many diabetic specialists recommend universal screening for GDM, it is agreed by all diabetologists that women at risk for GDM (women over age 25 who are overweight at the start of pregnancy; have a previous history of gestational diabetes; have had a previous infant weighing 9 lb or more at birth; have a history of a poor pregnancy outcome, glycosuria, or polycystic ovary syndrome; or who are from families or ethnic groups with a high incidence of type 2 DM) should undergo oral glucose tolerance testing as soon as possible to assess blood glucose levels while fasting and after meals. Testing should be repeated at 24 to 28 weeks' gestation if the first screening is negative.

Treatment

A calorically restricted diet, regular exercise, and metformin or insulin are used to treat GDM.

Patient care

Blood glucose self-monitoring is essential to management, and patients should be taught to monitor glucose levels four times each day, obtaining a fasting level in the morning, followed by three postprandial levels (1 hr after the start of each meal). Blood glucose levels at 1 hr after beginning a meal are considered the best predictor for subsequent fetal macrosomia. Target blood glucose levels are 90 mg/dL or less (fasting) and 120 to 140 mg/dL postprandially. The patient and her partner should be instructed that food, stress, inactivity, and hormones elevate blood glucose levels and that exercise and insulin lower them. They will need to learn about both pharmacological (measuring and injecting insulin) and nonpharmacological (menu management and physical activity) interventions to maintain a normal glycemic state (euglycemia) throughout the pregnancy, while ensuring adequate caloric intake for fetal growth and preventing maternal ketosis. Women who have no medical or obstetrical contraindicting factors should be encouraged to participate in an approved exercise program, because physical activity increases insulin receptor sensitivity. Even performing 15 to 20 min of “armchair exercises” daily (while reading or watching television) can help the pregnant woman reduce hyperglycemia without increasing the risk of inducing uterine contractions. If euglycemia is not achieved by nutrition therapy and exercise within 10 days, insulin is started. Pregnant women require three to four times the amount of insulin needed by a nonpregnant woman. Human minimally antigenic insulin should be prescribed. Often one dose of long-acting insulin at bedtime is sufficient, with rapid-acting insulins, i.e., regular insulin, insulin aspart recombinant (Novolog), or insulin lispro recombinant (Humalog) used to aid optimal glycemic control. Insulin glargine (Lantus), once used for gestational diabetes, is no longer recommended for pregnant women. Because stress can significantly raise blood glucose levels, stress management is a vital part of therapy. The woman’s feelings about her pregnancy and diabetes as well as her support system should be carefully assessed. Coping strategies should be explored. The patient is taught about deep breathing and relaxation exercises and encouraged to engage in activities that she enjoys and finds relaxing. She and her partner should learn to recognize interaction tensions and ways to deal with these to limit stress in their environment.

Maternal complications associated with GDM include pregnancy-induced hypertension, eclampsia, and the need for cesarean section delivery.

hybrid diabetes

iatrogenic diabetes

idiopathic diabetes

Type 1b diabetes.immune-mediated diabetes mellitus

Type 1 diabetes.diabetes insipidus

Abbreviation: DIEtiology

DI usually results from hypothalamic injury (such as brain trauma or neurosurgery) or from the effects of certain drugs (such as lithium or demeclocycline) on the renal resorption of water. Other representative causes include sickle cell anemia (in which renal infarcts damage the kidney's ability to retain water), hypothyroidism, adrenal insufficiency, inherited disorders of antidiuretic hormone production, and sarcoidosis.

Symptoms

The primary symptoms are urinary frequency, thirst, and dehydration.

Treatment

When DI is a side effect of drug therapy, the offending drug is withheld. DI caused by failure of the posterior pituitary gland to secrete antidiuretic hormone is treated with synthetic vasopressin.

Patient care

Fluid balance is monitored. Fluid intake and output, urine specific gravity, and weight are assessed for evidence of dehydration and hypovolemic hypotension. Serum electrolyte and blood urea nitrogen levels are monitored.

The patient is instructed in nasal insufflation of vasopressin (desmopressin acetate, effective for 8 to 20 hr, depending on dosage), the oral tablet form being more useful for bedtime or administration of subcutaneous or intramuscular vasopressin (effective for 2 to 6 hr). The length of the therapy and the importance of taking medications as prescribed and not discontinuing them without consulting the prescriber are stressed. Hydrochlorothiazide can be prescribed for nephrogenic DI not caused by drug therapy; amiloride may be used in nephrogenic DI caused by lithium administration. Meticulous skin and oral care are provided; use of a soft toothbrush is recommended; and petroleum jelly is applied to the lips and an emollient lotion to the skin to reduce dryness and prevent skin breakdown. Adequate fluid intake should be maintained.

Both the patient and family are taught to identify signs of dehydration and to report signs of severe dehydration and impending hypovolemia. The patient is taught to measure intake and output, to monitor weight daily, and to use a hydrometer to measure urine specific gravity. Weight gain should be reported because this may signify that the medication dosage is too high. Recurrence of polyuria may indicate dosing that is too low. The patient should wear or carry a medical ID tag and have prescribed medications with him or her at all times. Both patient and family need to know that chronic DI will not shorten the lifespan, but lifelong medications may be required to control the signs, symptoms, and complications of the disease. Counseling may be helpful in dealing with this chronic illness.

insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus

Abbreviation: IDDMType 1 diabetes.

juvenile-onset diabetes

latent diabetes

latent autoimmune diabetes in adults

Abbreviation: LADAmaternally inherited diabetes and deafness

See: maternally inherited diabetes and deafnessmature-onset diabetes of youth

Abbreviation: MODY

diabetes mellitus

Abbreviation: DMType 1 DM usually presents as an acute illness with dehydration and often diabetic ketoacidosis. Type 2 DM is often asymptomatic in its early years. The American Diabetes Association (1-800-DIABETES) estimates that more than 5 million Americans have type 2 DM without knowing it.

Etiology

Type 1 DM is caused by autoimmune destruction of the insulin-secreting beta cells of the pancreas. The loss of these cells results in nearly complete insulin deficiency; without exogenous insulin, type 1 DM is rapidly fatal. Type 2 DM results partly from a decreased sensitivity of muscle cells to insulin-mediated glucose uptake and partly from a relative decrease in pancreatic insulin secretion.

Symptoms

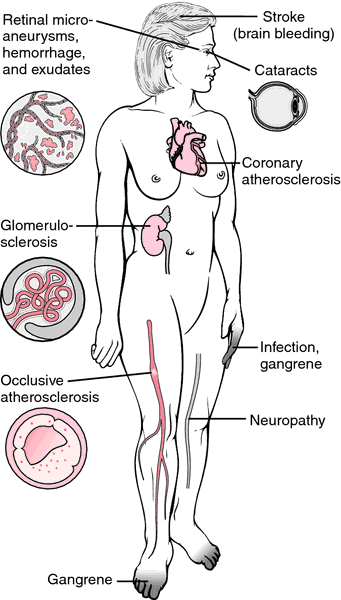

Classic symptoms of DM are polyuria, polydipsia, and weight loss. In addition, patients with hyperglycemia often have blurred vision, increased food consumption (polyphagia), and generalized weakness. When a patient with type 1 DM loses metabolic control (such as during infections or periods of noncompliance with therapy), symptoms of diabetic ketoacidosis occur. These may include nausea, vomiting, dizziness on arising, intoxication, delirium, coma, or death. Chronic complications of hyperglycemia include retinopathy and blindness, peripheral and autonomic neuropathies, glomerulosclerosis of the kidneys (with proteinuria, nephrotic syndrome, or end-stage renal failure), coronary and peripheral vascular disease, and reduced resistance to infections. Patients with DM often also sustain infected ulcerations of the feet, which may result in osteomyelitis and the need for amputation.

Diagnosis

Several tests are helpful in identifying DM. These include tests of fasting plasma glucose levels, casual (randomly assessed) glucose levels, or glycosylated hemoglobin levels. Diabetes is currently established if patients have classic diabetic symptoms and if on two occasions fasting glucose levels exceed 126 mg/dL (> 7 mmol/L), random glucose levels exceed 200 mg/dL (11.1 mmol/L), or a 2-hr oral glucose tolerance test is 200 mg/dL or more. A hemoglobin A1c test that is more than two standard deviations above normal (6.5% or greater) is also diagnostic of the disease.

Treatment

DM types 1 and 2 are both treated with specialized diets, regular exercise, intensive foot and eye care, and medications.

Patients with type 1 DM, unless they have had a pancreatic transplant, require insulin to live; intensive therapy with insulin to limit hyperglycemia (“tight control”) is more effective than conventional therapy in preventing the progression of serious microvascular complications such as kidney and retinal diseases. Intensive therapy consists of three or more doses of insulin injected or administered by infusion pump daily, with frequent self-monitoring of blood glucose levels as well as frequent changes in therapy as a result of contacts with health care professionals. Some negative aspects of intensive therapy include a three times more frequent occurrence of severe hypoglycemia, weight gain, and an adverse effect on serum lipid levels, i.e., a rise in total cholesterol, LDL cholesterol, and triglycerides and a fall in HDL cholesterol. Participation in an intensive therapy program requires a motivated patient, but it can dramatically reduce eye, nerve, and renal complications compared to conventional therapy. See: insulin pump for illus.

Some patients with type 2 DM can control their disease with a calorically restricted diet (for instance 1600 to 1800 cal/day), regular aerobic exercise, and weight loss. Most patients, however, require the addition of some form of oral hypoglycemic drug or insulin. Oral agents to control DM include sulfonylurea drugs (such as glipizide), which increase pancreatic secretion of insulin; biguanides or thiazolidinediones (such as metformin or pioglitazone), which increase cellular sensitivity to insulin; or a-glucosidase inhibitors (such as acarbose), which decrease the absorption of carbohydrates from the gastrointestinal tract. Both types of diabetics also may be prescribed pramlintide (Symlin), a synthetic analog of human amylin, a hormone manufactured in the pancreatic beta cells. It enhances postprandial glucose control by slowing gastric emptying, decreasing postprandial glucagon concentrations, and regulating appetite and food intake; thus pramlintide is helpful for patients who do not achieve optimal glucose control with insulin and/or oral antidiabetic agents. When combinations of these agents fail to normalize blood glucose levels, insulin injections are added. Tight glucose control can reduce the patient’s risk of many of the complications of the disease. See: illustration

Prevention of Complications

Patients with DM should avoid tobacco, actively manage their serum lipid levels, and keep hypertension under optimal control. Failure to do so may result in a risk of atherosclerosis much higher than that of the general public. Other elements in care include receiving regular vaccinations, e.g., to prevent influenza and pneumococcal pneumonia).

Prognosis

Diabetes is a chronic disease whose symptoms can be ameliorated and life prolonged by proper therapy. The isolation and eventual production of insulin in 1922 by Canadian physicians F. G. Banting and C. H. Best made it possible to allow people with the disease to lead normal lives.

Patient care

The diabetic patient should learn to recognize symptoms of low blood sugar (such as confusion, sweats, and palpitations) and high blood sugar (such as, polyuria and polydipsia). When either condition results in hospitalization, vital signs, weight, fluid intake, urine output, and caloric intake are accurately documented. Serum glucose and urine ketone levels are evaluated. Chronic management of DM is also based on periodic measurement of glycosylated hemoglobin levels (HbA1c). Elevated levels of HbA1c suggest poor long-term glucose control. The effects of diabetes on other body systems (such as cerebrovascular, coronary artery, and peripheral vascular) should be regularly assessed. Patients should be evaluated regularly for retinal disease and visual impairment and peripheral and autonomic nervous system abnormalities, e.g., loss of sensation in the feet. The patient is observed for signs and symptoms of diabetic neuropathy, e.g., numbness or pain in the hands and feet, decreased vibratory sense, footdrop, and neurogenic bladder. The urine is checked for microalbumin or overt protein losses, an early indication of nephropathy. The combination of peripheral neuropathy and peripheral arterial disease results in changes in the skin and microvasculature that lead to ulcer formation on the feet and lower legs with poor healing. Approx. 45,000 lower-extremity diabetic amputations are performed in the U.S. each year. Many amputees have a second amputation within five years. Most of these amputations are preventable with regular foot care and examinations. Diabetic patients and their providers should look for changes in sensation to touch and vibration, the integrity of pulses, capillary refill, and the skin. All injuries, cuts, and blisters should be treated promptly. The patient should avoid constricting hose, slippers, shoes, and bed linens or walking barefoot. The patient with ulcerated or insensitive feet is referred to a podiatrist for continuing foot care and is warned that decreased sensation can mask injuries.

Home blood glucose self-monitoring is indispensable in helping patients to adjust daily insulin doses according to test results and to achieve optimal long-term control of diabetes. Insulin or other hypoglycemic agents are administered as prescribed, and their action and use explained to the patient. With help from a dietitian, a diet is planned based on the recommended amount of calories, protein, carbohydrates, and fats. The amount of carbohydrates consumed is a dietary key to managing glycemic control in diabetes. For most men, 60 to 75 carbohydrate g per meal are a reasonable intake; for most women, 45 to 60 g are appropriate. Saturated fats should be limited to less than 7% of total caloric intake, and trans-fatty acids (unsaturated fats with hydrogen added) minimized. A steady, consistent level of daily exercise is prescribed, and participation in a supervised exercise program is recommended.

Hypoglycemic reactions are promptly treated by giving carbohydrates (orange juice, hard candy, honey, or any sugary food); if necessary, subcutaneous or intramuscular glucagon or intravenous dextrose (if the patient is not conscious) is administered. Hyperglycemic crises are treated initially with prescribed intravenous fluids and insulin and later with potassium replacement based on laboratory values.

Regular ophthalmological examinations are recommended for early detection of diabetic retinopathy. The patient is educated about diabetes, its possible complications and their management, and the importance of adherence to the prescribed therapy. The patient is taught the importance of maintaining normal blood pressure levels (120/80 mm Hg or lower). Control of even mild-to-moderate hypertension results in fewer diabetic complications, esp. nephropathy, cerebrovascular disease, and cardiovascular disease. Limiting alcohol intake to approximately one drink daily and avoiding tobacco are also important for self-management. Emotional support and a realistic assessment of the patient's condition are offered; this assessment should stress that, with proper treatment, the patient can have a near-normal lifestyle and life expectancy. Long-term goals for a patient with diabetes should include achieving and maintaining optimal metabolic outcomes to prevent complications; modifying diet and lifestyle to prevent and treat obesity, dyslipidemia, cardiovascular disease, hypertension, and nephropathy; improving physical activity; and allowing for the patient’s nutritional and psychosocial needs and preferences. Assistance is offered to help the patient develop positive coping strategies. It is estimated that 23 million Americans will be diabetic by the year 2030. The increasing prevalence of obesity coincides with the increasing incidence of diabetes; approx. 45% of those diagnosed receive optimal care according to established guidelines. According to the CDC, the NIH, and the ADA, about 40% of Americans between ages 40 and 74 have prediabetes, putting them at increased risk for type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease. Lifestyle changes with a focus on decreasing obesity can prevent or delay the onset of diabetes in 58% of this population. The patient and family should be referred to local and national support and information groups and may require psychological counseling.

| Diabetic Ketoacidosis | Hypoglycemia | |

|---|---|---|

| Onset | Gradual | Often sudden |

| History | Often acute infection in a diabetic or insufficient insulin intake | Recent insulin injection, inadequate meal, or excessive exercise after insulin |

| Previous history of diabetes may be absent | ||

| Musculoskeletal | Muscle wasting or weight loss | Weakness |

| Tremor | ||

| Muscle twitching | ||

| Gastrointestinal | Abdominal pains or cramps, sometimes acute | Nausea and vomiting |

| Nausea and vomiting | ||

| Central nervous system | Headache | Confusion, delirium, or seizures |

| Double or blurred vision | ||

| Irritability | ||

| Cardiovascular | Tachycardia | Variable |

| Orthostatic hypotension | ||

| Skin | Flushed, dry | Diaphoretic, pale |

| Respiratory | Air hunger | Variable |

| Acetone odor of breath | Increased respiratory rate | |

| Dyspnea | ||

| Laboratory values | Elevated blood glucose (> 200 mg/dL) | Subnormal blood glucose (0–50 mg/dL) |

| Glucose and ketones in blood and urine | Absence of glucose and ketones in urine unless bladder is full |

non–insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus

Abbreviation: NIDDMType 2 diabetes. See: type 1 diabetes for table

pancreatic diabetes

phlorhizin diabetes

renal diabetes

secondary diabetes mellitus

steroid diabetes

strict control of diabetes

Patients with meticulously controlled DM typically have a hemoglobin A1c level of 6.5 to 7.0 or lower, fasting blood sugars that are less than 110 mg/dL, and after-meal blood sugar readings that are 140 mg/dL or less.

tight control of diabetes

Strict control of diabetes.true diabetes

Diabetes mellitus.type 1 diabetes

| Type 1 | Type 2 | |

|---|---|---|

| Age at onset | Usually under 30 | Usually over 40 |

| Symptom onset | Abrupt | Gradual |

| Body weight | Normal | Obese—80% |

| HLA association | Positive | Negative |

| Family history | Common | Nearly universal |

| Insulin in blood | Little to none | Some usually present |

| Islet cell antibodies | Present at onset | Absent |

| Prevalence | 0.2–0.3% | 6% |

| Symptoms | Polyuria, polydipsia, polyphagia, weight loss, ketoacidosis | Polyuria, polydipsia, peripheral neuropathy |

| Control | Insulin, diet, and exercise | Diet, exercise, and often oral hypoglycemic drugs or insulin |

| Vascular and neural changes | Eventually develop | Will usually develop |

| Stability of condition | Fluctuates, may be difficult to control | May be difficult to control in poorly motivated patients |

type 1a diabetes mellitus

type 1b diabetes mellitus

type 2 diabetes

unstable diabetes mellitus

Brittle diabetes.diabetes

See DIABETES MELLITUS.diabetes

a metabolic disorder, either where there is an increase in the amount of urine excreted (diabetes insipidus), or where excess sugar appears in the blood and urine, associated with thirst and loss of weight (diabetes mellitus). The former is caused by the failure of the pituitary to secrete ADH, and the latter by the failure of the ISLETS OF LANGERHANS to produce sufficient insulin.Diabetes

diabetes

di·a·be·tes

(dī-ă-bē'tēz) Avoid using the simple word diabetes for diabetes mellitus unless the sense is clear from the context.Patient discussion about diabetes

Q. My 7yr has Diabetes. She been Diabetic for about 5 weeks and we can't get numbers at a good spot. she aether way to low (30- 60 scary when she gets like this) and to high (300 - 400) We been looking at what she eating calling the physician. he been play with here shots but nothing working. Its when she at school is were the nuber are mostly going up an down. we been trying to work with the school but she the only one in the hole school that has Diabetes. what to do ?

Keep an eye on her, but don't make it sound like such a big deal.

Q. how diabetes is caused

for further information please visit:

http://healthy-ojas.com/html/diabetes_mellitus.html

Here we can find information on alternative medicines for diabetes.

Q. my grandmother was diabetic ... and i learned that diabetic is genetic ... should i be concern for me or or for one of my family reletives ... she suffered a lot and she died of it .. if a blood tests shows high amount of sugar in my blood , does i mean i am diabetic ?

More discussions about diabetesLatest Searches:

zoopharmacy - zoopharmacology - zoophagous - zoopery - zooperal - zoopathology - zooparasitica - zooparasitic - zooparasite - zoonotic - zoonosology - Zoonosis - zoonoses - zoonomy - zoonite - zoonerythrin - zoomastigophorean - Zoomastigophorea - Zoomastigophora - zoomania -

- Service manuals - MBI Corp