Medical term:

sicklemia

anemia

[ah-ne´me-ah]a condition in which there is reduced delivery of oxygen to the tissues; it is not actually a disease but rather a symptom of any of numerous different disorders and other conditions. The World Health Organization has defined anemia as a hemoglobin concentration below 7.5 mmol/L (12 g/dL) in women and below 8.1 mmol/L (13 g/dL) in men.

Some types of anemia are named for the factors causing them: poor diet (nutritional anemia), excessive blood loss (hemorrhagic anemia), congenital defects of hemoglobin (hypochromic anemia), exposure to industrial poisons, diseases of the bone marrow (aplastic anemia and hypoplastic anemia), or any other disorder that upsets the balance between blood loss through bleeding or destruction of blood cells and production of blood cells. Anemias can also be classified according to the morphologic characteristics of the erythrocytes, such as size (microcytic, macrocytic, and normocytic anemias) and color or hemoglobin concentration (hypochromic anemia). A type called hypochromic microcytic anemia is characterized by very small erythrocytes that have low hemoglobin concentration and hence poor coloration. Data used to identify anemia types include the erythrocyte indices: (1) mean corpuscular volume (MCV), the average erythrocyte volume; (2) mean corpuscular hemoglobin (MCH), the average amount of hemoglobin per erythrocyte; and (3) mean corpuscular hemoglobin concentration (MCHC), the average concentration of hemoglobin in erythrocytes. adj., adj ane´mic.

Activity intolerance is a common problem for patients with anemia. Physical activity increases demand for oxygen, but if there are not enough circulating erythrocytes to provide sufficient oxygen, patients become physically weak and unable to engage in normal physical activity without experiencing profound fatigue. This can result in some degree of self-care deficit as the fatigue interferes with the patient's ability to carry on regular or enjoyable activities.

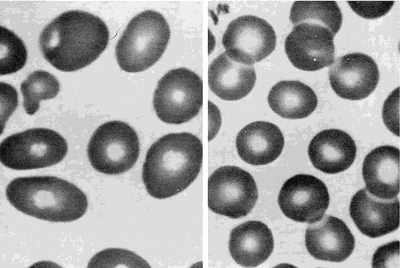

Peripheral blood smears from a patient with megaloblastic anemia (left) and from a normal subject (right), both at the same magnification. The smear from the patient shows variation in the size and shape of erythrocytes and the presence of macro-ovalocytes. From Goldman and Bennett, 2000.

Some types of anemia are named for the factors causing them: poor diet (nutritional anemia), excessive blood loss (hemorrhagic anemia), congenital defects of hemoglobin (hypochromic anemia), exposure to industrial poisons, diseases of the bone marrow (aplastic anemia and hypoplastic anemia), or any other disorder that upsets the balance between blood loss through bleeding or destruction of blood cells and production of blood cells. Anemias can also be classified according to the morphologic characteristics of the erythrocytes, such as size (microcytic, macrocytic, and normocytic anemias) and color or hemoglobin concentration (hypochromic anemia). A type called hypochromic microcytic anemia is characterized by very small erythrocytes that have low hemoglobin concentration and hence poor coloration. Data used to identify anemia types include the erythrocyte indices: (1) mean corpuscular volume (MCV), the average erythrocyte volume; (2) mean corpuscular hemoglobin (MCH), the average amount of hemoglobin per erythrocyte; and (3) mean corpuscular hemoglobin concentration (MCHC), the average concentration of hemoglobin in erythrocytes. adj., adj ane´mic.

Symptoms. Mild degrees of anemia often cause only slight and vague symptoms, perhaps nothing more than easy fatigue or a lack of energy. As the condition progresses, more severe symptoms may be experienced, such as shortness of breath, pounding of the heart, and a rapid pulse; these are caused by the inability of anemic blood to supply the body tissues with enough oxygen. Pallor, particularly in the palms of the hands, the fingernails, and the conjunctiva (the lining of the eyelids), may also indicate anemia. In very advanced cases, swelling of the ankles and other evidence of heart failure may appear.

Common Causes of Anemia. Loss of Blood (Hemorrhagic Anemia): If there is massive bleeding from a wound or other lesion, the body may lose enough blood to cause severe and acute anemia, which is often accompanied by shock. Immediate transfusions are generally required to replace the lost blood. Chronic blood loss, such as excessive menstrual flow, or slow loss of blood from an ulcer or cancer of the gastrointestinal tract, may also lead to anemia. These anemias disappear when the cause has been found and corrected. To help the blood replenish itself, the health care provider may prescribe medicines containing iron, which is necessary to build hemoglobin, and foods with high iron content, such as kidney and navy beans, liver, spinach, and whole wheat bread.

Dietary Deficiencies and Abnormalities of Red Blood Cell Production (Nutritional Anemia, Aplastic Anemia, and Hypoplastic Anemia): Anemia may develop if the diet does not provide enough iron, protein, vitamin B12, and other vitamins and minerals needed in the production of hemoglobin and the formation of erythrocytes. The combination of poor diet and chronic loss of blood makes for particular susceptibility to severe anemia. Anemias associated with folic acid deficiency are very common.

Excessive Destruction of Red Blood Cells (hemolytic anemia): Anemia may also develop related to hemolysis due to trauma, chemical agents or medications (toxic hemolytic anemia), infectious disease, isoimmune hemolytic reactions, autoimmune disorders, and the paroxysmal hemoglobinurias.

Dietary Deficiencies and Abnormalities of Red Blood Cell Production (Nutritional Anemia, Aplastic Anemia, and Hypoplastic Anemia): Anemia may develop if the diet does not provide enough iron, protein, vitamin B12, and other vitamins and minerals needed in the production of hemoglobin and the formation of erythrocytes. The combination of poor diet and chronic loss of blood makes for particular susceptibility to severe anemia. Anemias associated with folic acid deficiency are very common.

Excessive Destruction of Red Blood Cells (hemolytic anemia): Anemia may also develop related to hemolysis due to trauma, chemical agents or medications (toxic hemolytic anemia), infectious disease, isoimmune hemolytic reactions, autoimmune disorders, and the paroxysmal hemoglobinurias.

Patient Care. Assessment of patients with some form of anemia will depend to some extent on the specific type of blood dyscrasia presented. In general, these patients do share some common problems requiring special assessment skills and interventions. Anemia can affect many different body systems

(see table). Although pallor of the skin is a sign of anemia, it is not the most reliable sign; many other factors can affect complexion and skin color. Jaundice of the skin and sclera can occur as a result of hemolysis and the release of bilirubin into the blood stream, where it eventually finds its way into the skin and mucous membranes. (See also jaundice.) Bleeding under the skin and bruises in response to the slightest trauma often are present in anemic and leukemic patients. A bluish tint to the skin (cyanosis) can indicate hypoxia due to inadequate numbers of oxygen-bearing erythrocytes.Activity intolerance is a common problem for patients with anemia. Physical activity increases demand for oxygen, but if there are not enough circulating erythrocytes to provide sufficient oxygen, patients become physically weak and unable to engage in normal physical activity without experiencing profound fatigue. This can result in some degree of self-care deficit as the fatigue interferes with the patient's ability to carry on regular or enjoyable activities.

acute posthemorrhagic anemia hemorrhagic anemia.

aplastic anemia see aplastic anemia.

autoimmune hemolytic anemia (AIHA) an acquired disorder characterized by hemolysis due to the production of autoantibodies against one's own red blood cell antigens.

Blackfan-Diamond anemia congenital hypoplastic anemia (def. 1).

congenital hypoplastic anemia

idiopathic progressive anemia occurring in the first year of life, without leukopenia and thrombocytopenia; it is due to an isolated defect in erythropoiesis and is unresponsive to hematinics, requiring multiple blood transfusions to sustain life. For those responding to steroid therapy the prognosis is good. Called also Blackfan-Diamond anemia or syndrome, Diamond-Blackfan anemia or syndrome, and erythrogenesis imperfecta.

Fanconi's syndrome (def. 1).

Cooley's anemia tthalassemia major.

deficiency anemia nutritional anemia.

Diamond-Blackfan anemia congenital hypoplastic anemia (def. 1).

drug-induced hemolytic anemia (drug-induced immune hemolytic anemia) a form of immune hemolytic anemia induced by the taking of drugs, involving one of four different mechanisms:

Immune complex problems: Ingestion of any of a large number of drugs is followed by immunization and the formation of a soluble drug–anti-drug complex that adsorbs nonspecifically to the erythrocyte surface.

Drug absorption: Drugs bind firmly to erythrocyte membrane proteins, inducing the formation of specific antibodies; the drug most commonly associated with this mechanism is penicillin.

Membrane modification: A nonimmunologic mechanism whereby the drug involved is able to modify erythrocytes so that plasma proteins can bind to the membrane.

Autoantibody formation: Methyldopa (Aldomet) induces the production of autoantibodies that recognize erythrocyte antigens and are serologically indistinguishable from those seen in patients with warm autoimmune hemolytic anemia.

Immune complex problems: Ingestion of any of a large number of drugs is followed by immunization and the formation of a soluble drug–anti-drug complex that adsorbs nonspecifically to the erythrocyte surface.

Drug absorption: Drugs bind firmly to erythrocyte membrane proteins, inducing the formation of specific antibodies; the drug most commonly associated with this mechanism is penicillin.

Membrane modification: A nonimmunologic mechanism whereby the drug involved is able to modify erythrocytes so that plasma proteins can bind to the membrane.

Autoantibody formation: Methyldopa (Aldomet) induces the production of autoantibodies that recognize erythrocyte antigens and are serologically indistinguishable from those seen in patients with warm autoimmune hemolytic anemia.

Fanconi's anemia (Fanconi's hypoplastic anemia) Fanconi's syndrome (def. 1).

hemolytic anemia see hemolytic anemia.

hemorrhagic anemia anemia caused by the sudden and acute loss of blood; called also acute posthemorrhagic anemia.

hypochromic anemia anemia in which the decrease in hemoglobin is proportionately much greater than the decrease in number of erythrocytes.

hypochromic microcytic anemia any anemia with microcytes that are hypochromic (reduced in size and in hemoglobin content); the most common type is iron deficiency anemia.

hypoplastic anemia anemia due to incapacity of blood-forming organs.

immune hemolytic anemia an acquired hemolytic anemia in which a hemolytic response is caused by isoantibodies or autoantibodies produced on exposure to drugs, toxins, or other antigens. See also autoimmune hemolytic anemia, drug-induced immune hemolytic anemia, and erythroblastosis fetalis.

iron deficiency anemia a type of hypochromic microcytic anemia that results from the presence of greater demands on stored iron than can be met, usually because of chronic blood loss, dietary deficiency, or defective absorption; it is characterized by low or absent iron stores, low serum iron concentration, low transferrin saturation, elevated transferrin (total iron-binding capacity), and low hemoglobin concentration or hematocrit. Iron deficiency anemia is the most common nutritional disorder in the United States.

macrocytic anemia anemia characterized by macrocytes (erythrocytes much larger than normal).

Mediterranean anemia thalassemia major.

megaloblastic anemia any of various anemias characterized by the presence of megaloblasts in the bone marrow or blood; the most common type is pernicious anemia.

microangiopathic hemolytic anemia thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura.

microcytic anemia anemia characterized by microcytes (erythrocytes smaller than normal); see also hypochromic microcytic anemia and microcythemia.

myelopathic anemia (myelophthisic anemia) leukoerythroblastosis.

normochromic anemia that in which the hemoglobin content of the red blood cells is in the normal range.

normocytic anemia anemia characterized by proportionate decrease in hemoglobin, packed red cell volume, and number of erythrocytes per cubic millimeter of blood.

nutritional anemia anemia due to a deficiency of an essential substance in the diet, which may be caused by poor dietary intake or by malabsorption; called also deficiency anemia.

pernicious anemia see pernicious anemia.

sickle cell anemia see sickle cell anemia.

sideroachrestic anemia (sideroblastic anemia) any of a heterogenous group of acquired and hereditary anemias with diverse clinical manifestations, commonly characterized by large numbers of sideroblasts in the bone marrow, ineffective erythropoiesis, variable proportions of hypochromic erythrocytes in the peripheral blood, and usually increased levels of tissue iron.

spur cell anemia anemia in which the erythrocytes are acanthocytes (spur cells) and are destroyed prematurely, primarily in the spleen; it is an acquired form occurring in severe liver disease in which there is increased serum cholesterol and increased uptake of cholesterol into the erythrocyte membrane, causing the abnormal shape.

sickle cell

a crescentic or sickle-shaped erythrocyte, the abnormal shape caused by the presence of varying proportions of hemoglobin S. See illustration at cell.

sickle cell anemia an autosomal dominant, chronic form of hemolytic anemia in which large numbers of sickle cells circulate in the blood; it is most common among persons of African and Mediterranean descent. Persons genetically homozygous have 85 to 95 per cent sickle cells and have the full-blown condition; see sickle cell disease. Those who are heterozygous are usually asymptomatic.

sickle cell crisis a broad term describing several different acute conditions occurring as part of sickle cell disease, such as aplastic crisis, hemolytic crisis, and vaso-occlusive crisis.

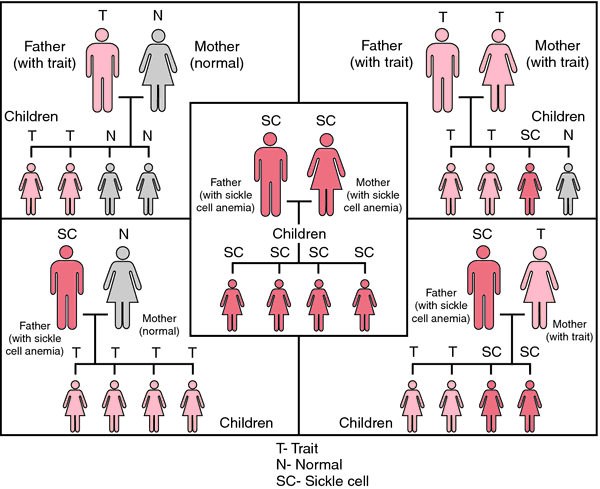

sickle cell disease any of the diseases associated with the presence of hemoglobin S, including sickle cell anemia, sickle cell–thalassemia, and the conditions called sickle cell–hemoglobin C and D disease. They are found most often in those of black African descent, but they also occur in persons of Mediterranean (Southern European and North African), Middle Eastern, or Asian Indian ancestry. About 8 to 10 per cent of all African Americans carry the sickle cell gene. About 90 per cent of persons with the gene are heterozygous for it, simply carriers of the sickle cell trait and usually without symptoms. The remainder, or about 1 in 500 of an ethnic group where the gene occurs, are homozygous for hemoglobin S, actually having sickle cell disease and suffering from the effects of hemolysis.

Sickle cell disease is a serious, hereditary, chronic disease in which the red blood cells have reduced life span and are rigid, with a crescent or sickle shape. The shape is the result of an abnormality in the hemoglobin, which alters the deformability of the cells under conditions of low oxygen tension. Because of their distorted shape the cells have difficulty passing through the small arterioles and capillaries and have a tendency to clump together and occlude the blood vessel. Some scientists believe that sickle cell disease developed as a defense against malaria. Malarial parasites do not grow in erythrocytes containing hemoglobin S. Therefore, carriers (heterozygotes) have an advantage in areas where malaria is prevalent (called the heterozygote advantage). (See accompanying figure.)

Sickle cell disease is a serious, hereditary, chronic disease in which the red blood cells have reduced life span and are rigid, with a crescent or sickle shape. The shape is the result of an abnormality in the hemoglobin, which alters the deformability of the cells under conditions of low oxygen tension. Because of their distorted shape the cells have difficulty passing through the small arterioles and capillaries and have a tendency to clump together and occlude the blood vessel. Some scientists believe that sickle cell disease developed as a defense against malaria. Malarial parasites do not grow in erythrocytes containing hemoglobin S. Therefore, carriers (heterozygotes) have an advantage in areas where malaria is prevalent (called the heterozygote advantage). (See accompanying figure.)

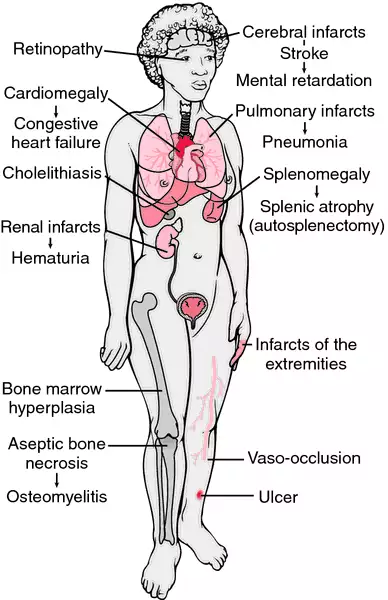

Symptoms. There are many symptoms of sickle cell disease, all of them related to the defective hemoglobin and its effect on red blood cells. Some persons with the condition suffer from only a few symptoms, while others are severely affected and have a short life span. Better understanding and management of the disease in recent decades has improved the prognoses for patients with it.

The major symptoms are anemia, periodic joint and limb pain and sometimes edema of the joints, chronic ulceration about the ankles, episodes of severe abdominal pain with vomiting, and abdominal distention. The spleen becomes infarcted so that it is essentially absent and predisposes the patient to infection with encapsulated organisms. Bone changes often can be seen on x-ray and are due to bone infarcts. Headache, paralysis, and convulsions may result from cerebral thrombosis, which can cause stroke, blindness, and other neurological disturbances. There is a tendency toward progressive renal disease and renal failure.

The major symptoms are anemia, periodic joint and limb pain and sometimes edema of the joints, chronic ulceration about the ankles, episodes of severe abdominal pain with vomiting, and abdominal distention. The spleen becomes infarcted so that it is essentially absent and predisposes the patient to infection with encapsulated organisms. Bone changes often can be seen on x-ray and are due to bone infarcts. Headache, paralysis, and convulsions may result from cerebral thrombosis, which can cause stroke, blindness, and other neurological disturbances. There is a tendency toward progressive renal disease and renal failure.

Sickle cell crisis is a broad term that describes several different conditions, particularly aplastic crisis, which is temporary bone marrow aplasia; hemolytic crisis, which is acute red cell destruction, leading to jaundice; and vaso-occlusive crisis, which is severe pain due to infarctions located in the bones, joints, lungs, liver, spleen, kidney, eye, or central nervous system. Factors that precipitate a crisis include infection, dehydration, trauma, strenuous physical exertion, emotional stress, and extremes of heat and cold.

Treatment and Care. There is no cure for sickle cell disease. Treatment is symptomatic; preventive measures are employed to reduce the incidence of crises and to avoid infections. It is also important that the patient receive all available immunizing agents. Nutritional deficiencies should be corrected when present (folate supplementation is especially important), and then a well-balanced dietary intake should be maintained. hydroxyurea and prophylactic penicillin are administered according to therapeutic guidelines. Social service programs are required to facilitate adjustment to the disease and its sequelae. Control of pain associated with this condition should be a priority.

Because of the potential for serious complications due to occlusion of blood vessels, patients with sickle cell disease should have regular physical examinations to detect early changes. Periodic eye examinations are necessary to monitor retinal changes due to vaso-occlusion of retinal vessels.

Measures to improve or maintain the general well-being of patients include preventing dehydration, maintaining adequate nutrition to optimize the patient's resistance to infection and resources for healing, and managing the anemia that is characteristic of sickle cell disease. Education of patients and their parents and family members is an essential component of care. Patient support groups can be an effective mechanism to diffuse fear. Guidelines for the management of acute and chronic pain are available from the American Pain Society. A comprehensive biopsychosocial clinical assessment should be performed at least yearly.

The National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute of NIH has published a guide called NIH Management and Therapy of Sickle Cell Disease. A printed copy is available as NIH publication number 95-2117. The guidelines are available online at http://www.emory.edu/peds/sickle/nih1/htm.

Patient Care.

Sickle cell disease is a chronic condition with acute episodes related to vaso-occlusion. Virtually every system of the body can be affected by the ischemia resulting from obstruction of the blood vessels by clumps of deformed erythrocytes. Among the more common acute complications are inflammation of fingers and toes, aplastic anemia, splenic sequestration, and stroke. Chronic disorders include leg ulcers, renal complications, aseptic necrosis, and retinopathy. Bacterial infection is one of the major causes of morbidity and mortality in patients with sickle cell disease.Because of the potential for serious complications due to occlusion of blood vessels, patients with sickle cell disease should have regular physical examinations to detect early changes. Periodic eye examinations are necessary to monitor retinal changes due to vaso-occlusion of retinal vessels.

Measures to improve or maintain the general well-being of patients include preventing dehydration, maintaining adequate nutrition to optimize the patient's resistance to infection and resources for healing, and managing the anemia that is characteristic of sickle cell disease. Education of patients and their parents and family members is an essential component of care. Patient support groups can be an effective mechanism to diffuse fear. Guidelines for the management of acute and chronic pain are available from the American Pain Society. A comprehensive biopsychosocial clinical assessment should be performed at least yearly.

The National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute of NIH has published a guide called NIH Management and Therapy of Sickle Cell Disease. A printed copy is available as NIH publication number 95-2117. The guidelines are available online at http://www.emory.edu/peds/sickle/nih1/htm.

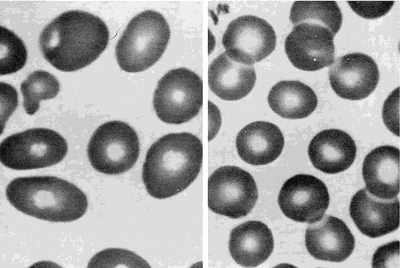

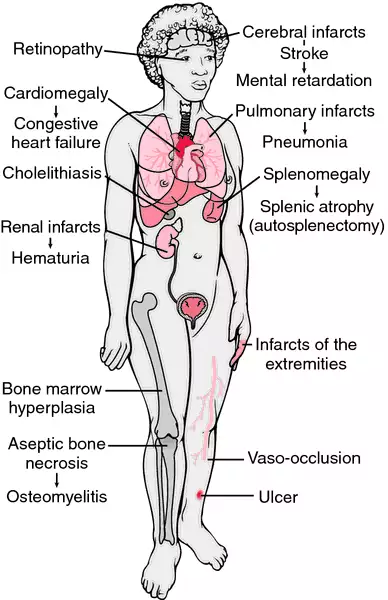

Clinicopathologic findings in sickle cell anemia. The findings are a consequence of infarctions, anemia, hemolysis, and recurrent infection. From Damjanov, 2000.

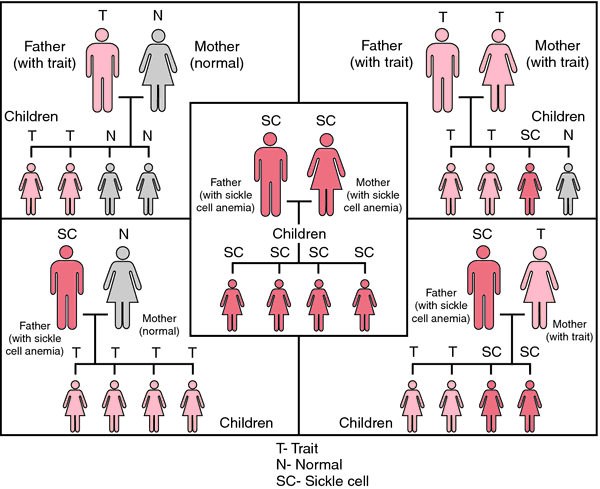

Statistical probabilities of inheriting sickle cell anemia.

sickle cell disorders any blood disorders associated with the presence of hemoglobin S, including the sickle cell diseases and sickle cell trait.

Miller-Keane Encyclopedia and Dictionary of Medicine, Nursing, and Allied Health, Seventh Edition. © 2003 by Saunders, an imprint of Elsevier, Inc. All rights reserved.

sick·le·mi·a

(sik-lē'mē-ă),Presence of sickle-shaped or crescentic erythrocytes in peripheral blood; seen in sickle cell anemia and sickle cell trait.

Farlex Partner Medical Dictionary © Farlex 2012

sicklemia

(sĭk′ə-lē′mē-ə)n.

Sickle cell anemia or sickle cell trait.

The American Heritage® Medical Dictionary Copyright © 2007, 2004 by Houghton Mifflin Company. Published by Houghton Mifflin Company. All rights reserved.

sick·le·mi·a

(sik-lē'mē-ă)Presence of sickle- or crescent-shaped erythrocytes in peripheral blood; seen in sickle cell anemia and sickle cell trait.

Synonym(s): sicklaemia.

Synonym(s): sicklaemia.

Medical Dictionary for the Health Professions and Nursing © Farlex 2012

sick·le·mi·a

(sik-lē'mē-ă)Presence of sickle- or crescent-shaped erythrocytes in peripheral blood; seen in sickle cell anemia and sickle cell trait.

Synonym(s): sicklaemia.

Synonym(s): sicklaemia.

Medical Dictionary for the Dental Professions © Farlex 2012

Patient discussion about sicklemia

Q. Please precribe for me the possible medicine (treatment) for sickle cells. Secondly, my boy lost hearing at 4 1- I need to know how sickle cells can be treated. 2- My boy just surprisingly lost his abillity to hear anything at the age of 4.

A. wow...you are going through some hard times...it's the hardest thing in the world seeing your children in pain. loosing his hearing could be caused by clots that were formed and destroyed the ear nerve. but it's unlikely it happened in both ears...so i would check it out. and about treatment- there are a variety of treatments, so i found a web site with them all. and even some that are still in research: http://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health/dci/Diseases/Sca/SCA_Treatments.html

More discussions about sicklemiaThis content is provided by iMedix and is subject to iMedix Terms. The Questions and Answers are not endorsed or recommended and are made available by patients, not doctors.

Latest Searches:

Voraxaze - Voranil - Voorhoeve - voodoo - VOO - Vontrol - von - vomitus - vomiturition - vomitory - vomitoria - vomito - vomitive - vomiting - vomit - vomica - vomerovaginalis - vomerovaginal - vomerorostralis - vomerorostral -

- Service manuals - MBI Corp