Medical term:

Lithotripsy

Lithotripsy

Definition

Lithotripsy is the use of high-energy shock waves to fragment and disintegrate kidney stones. The shock wave, created by using a high-voltage spark or an electromagnetic impulse, is focused on the stone. This shock wave shatters the stone and this allows the fragments to pass through the urinary system. Since the shock wave is generated outside the body, the procedure is termed extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy, or ESWL.

Purpose

ESWL is used when a kidney stone is too large to pass on its own, or when a stone becomes stuck in a ureter (a tube which carries urine from the kidney to the bladder) and will not pass. Kidney stones are extremely painful and can cause serious medical complications if not removed.

Precautions

ESWL should not be considered for patients with severe skeletal deformities, patients weighing over 300 lbs (136 kg), patients with abdominal aortic aneurysms, or patients with uncontrollable bleeding disorders. Patients who are pregnant should not be treated with ESWL. Patients with cardiac pacemakers should be evaluated by a cardiologist familiar with ESWL. The cardiologist should be present during the ESWL procedure in the event the pacemaker needs to be overridden.

Description

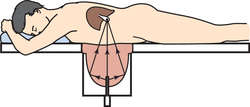

Lithotripsy uses the technique of focused shock waves to fragment a stone in the kidney or the ureter. The patient is placed in a tub of water or in contact with a water-filled cushion, and a shock wave is created which is focused on the stone. The wave shatters and fragments the stone. The resulting debris, called gravel, then passes through the remainder of the ureter, through the bladder, and through the urethra during urination. There is minimal chance of damage to skin or internal organs because biologic tissues are resilient, not brittle, and because the the shock waves are not focused on them.

Preparation

Prior to the lithotripsy procedure, a complete physical examination is done, followed by tests to determine the number, location, and size of the stone or stones. A test called an intravenous pyelogram, or IVP, is used to locate the stones. An IVP involves injecting a dye into a vein in the arm. This dye, which shows up on x ray, travels through the bloodstream and is excreted by the kidneys. The dye then flows down the ureters and into the bladder. The dye surrounds the stones, and x rays are then used to evaluate the stones and the anatomy of the urinary system. (Some people are allergic to the dye material, so it cannot be used. For these people, focused sound waves, called ultrasound, can be used to see where the stones are located.) Blood tests are done to determine if any potential bleeding problems exist. For women of childbearing age, a pregnancy test is done to make sure the patient isn't pregnant; and elderly patients have an EKG done to make sure no potential heart problems exist. Some patients may have a stent placed prior to the lithotripsy procedure. A stent is a plastic tube placed in the ureter which allows the passage of gravel and urine after the ESWL procedure is completed.

Key terms

Aneurysm — A dilation of the wall of an artery which causes a weak area prone to rupturing.

Bladder — Organ in which urine is stored prior to urination.

Bleeding disorder — Problems in the clotting mechanism of the blood.

Cardiologist — A physician who specializes in problems of the heart.

EKG — A tracing of the electrical activity of the heart.

ESWL (Extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy) — The use of focused shock waves, generated outside the body, to fragment kidney stones.

Gravel — The debris which is formed from a fragmented kidney stone.

IVP (Intravenous pyelogram) — The use of a dye, injected into the veins, used to locate kidney stones. Also used to determine the anatomy of the urinary system.

Kidney stone — A hard mass that forms in the urinary tract and which can cause pain, bleeding, obstruction, or infection. Stones are primarily made up of calcium.

Stent — A plastic tube placed in the ureter prior to the ESWL procedure which facilitates the passage of gravel and urine

Ultrasound — Sound waves used to determine the internal structures of the body

Ureter — A tube which carries urine from the kidney to the bladder.

Urethra — A tube through which urine passes during urination.

Urologist — A physician who specializes in problems of the urinary system.

Aftercare

Most patients have a lot of blood in their urine after the ESWL procedure. This is normal and should clear after several days to a week or so. Lots of fluids should be taken to encourage the flushing of any gravel remaining in the urinary system. The patient should follow up with the urologist in about two weeks to make sure that everything is going as planned. If a stent has been inserted, it is normally removed at this time. Patients may return to work whenever they feel able.

Risks

Abdominal pain is not uncommon after ESWL, but it is usually not cause to worry. However, persistent or severe abdominal pain may imply unexpected internal injury. Colicky renal pain is very common as gravel is still passing. Other problems may include perirenal hematomas (blood clots near the kidneys) in 66% of the cases; nerve palsies; pancreatitis (inflammation of the pancreas); and obstruction by stone fragments. Occasionally, stones may not be completely fragmented during the first ESWL treatment and further ESWL procedures may be required.

Resources

Organizations

American Urological Association. 1120 North Charles St., Baltimore, MD 21201-5559. (410) 727-1100. 〈http://www.auanet.org/index_hi.cfm〉.

Gale Encyclopedia of Medicine. Copyright 2008 The Gale Group, Inc. All rights reserved.

lithotripsy

[lith´o-trip″se]the crushing of calculi in the bladder, urethra, kidney, or gallbladder.

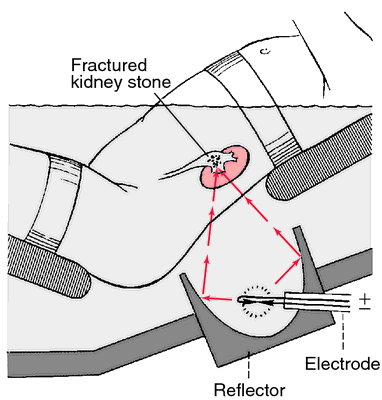

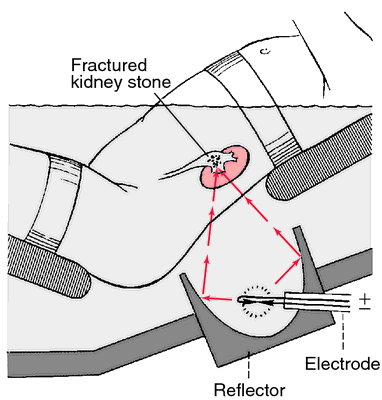

electrohydraulic lithotripsy a method used for large upper urinary tract calculi: a high-capacity condenser creates a high-voltage spark between two electrodes at the tip of a probe; in a fluid-filled organ this creates a hydraulic shock wave that can be directed toward a calculus, causing it to cavitate and fragment.

extracorporeal shock-wave lithotripsy (ESWL) a noninvasive fragmentation of kidney stones or gallstones with shock waves generated outside the body. It requires no incisions, catheters, or nephroscopes. The technique is based on the principle that shock waves are not destructive until they reach a surface in which there is a change in acoustical impedance, which is a form of resistance to the passage of sound waves. The impedance of calculi is different from that of water, bone, and soft tissue; therefore, tissue through which the wave travels as well as tissues surrounding the stone are not harmed.

For kidney stones, ESWL shatters the calculi into particles small enough to be passed in the urine. The procedure takes no longer than one to two hours, permits a shorter hospital stay, and allows the patient to return to normal life without delay.

ESWL is not appropriate for every patient with kidney stones. Body structure may prohibit proper positioning in the tank of water in which the patient must be submerged. Other contraindications include calcium deposits in the arteries, obstruction to urine flow, which is depended upon to flush out the fragments, and exaggerated spinal curvature, which interferes with visualization on x-ray. Stones that are not radiopaque cannot be treated by ESWL unless a radiopaque contrast medium is used because otherwise they cannot be seen and the shock waves cannot be properly focused on them. Very large stones (over one and a quarter inches in diameter) are not amenable to ESWL because they require more energy than the equipment can generate to break them into pieces small enough to travel through the urinary tract.

Complications such as obstruction to urine flow, bleeding, infection, and pain are less for ESWL than for other modes of therapy. The most formidable obstacle to widespread use of ESWL is the cost of the equipment.

For treatment of gallstones, the lithotriptor is used in combination with an ultrasound probe. The probe locates the calculi and the lithotriptor is fired. The fragments of gallstone traverse the biliary tract and are excreted via the intestines.

For kidney stones, ESWL shatters the calculi into particles small enough to be passed in the urine. The procedure takes no longer than one to two hours, permits a shorter hospital stay, and allows the patient to return to normal life without delay.

ESWL is not appropriate for every patient with kidney stones. Body structure may prohibit proper positioning in the tank of water in which the patient must be submerged. Other contraindications include calcium deposits in the arteries, obstruction to urine flow, which is depended upon to flush out the fragments, and exaggerated spinal curvature, which interferes with visualization on x-ray. Stones that are not radiopaque cannot be treated by ESWL unless a radiopaque contrast medium is used because otherwise they cannot be seen and the shock waves cannot be properly focused on them. Very large stones (over one and a quarter inches in diameter) are not amenable to ESWL because they require more energy than the equipment can generate to break them into pieces small enough to travel through the urinary tract.

Complications such as obstruction to urine flow, bleeding, infection, and pain are less for ESWL than for other modes of therapy. The most formidable obstacle to widespread use of ESWL is the cost of the equipment.

For treatment of gallstones, the lithotriptor is used in combination with an ultrasound probe. The probe locates the calculi and the lithotriptor is fired. The fragments of gallstone traverse the biliary tract and are excreted via the intestines.

Extracorporeal shock-wave lithotripsy. Electrically generated shock waves can fracture renal calculi. From Polaski and Tatro, 1996.

percutaneous ultrasonic lithotripsy (PUL) surgical removal of kidney stones via an incision and insertion of a nephroscope into the portion of the kidney where the stone is lodged. An attempt is first made to remove the calculus through the endoscope by basket or forceps. If this is not successful, an ultrasonic lithotrite that sends out high-frequency sound waves is used to break up the stone. A continuous saline irrigation flushes out the particles, which are removed by suction. The drainage is filtered to trap the particles so that they can be sent to the laboratory for analysis.

Advantages of PUL over conventional surgical procedures for removal of kidney stones are fewer complications, a surgical incision less than 1 to 2 cm long as compared to one 20 cm long, shorter hospital stay, and more rapid recovery.

Advantages of PUL over conventional surgical procedures for removal of kidney stones are fewer complications, a surgical incision less than 1 to 2 cm long as compared to one 20 cm long, shorter hospital stay, and more rapid recovery.

Patient Care. Preoperative care is fairly routine. The procedure usually is done in the radiology department and may be done in one or two stages. In the first stage the incision is made under local anesthesia and the nephrostomy catheter is inserted. In the second stage a general or epidural anesthetic is used and the ultrasonic lithotrite or “wand” is passed through the nephroscope. Ultrasonic waves of approximately 25,000 hertz are thus focused on the stone, breaking up its crystalline structure.

After surgery the vital signs are monitored to detect evidence of bleeding or infection. Some bright red blood in the urine passing through the nephrostomy can be expected for one to three days, but the amount of blood should gradually diminish. As bleeding subsides the urine becomes smoky and tinged with old blood. The kidney is a highly vascular organ and postoperative hemorrhage is always a threat.

If the patient has either a Foley catheter or a ureteral catheter or both remaining in place after surgery, they must be kept open and draining. Irrigations, if ordered, are done gently to avoid excessive bleeding. A decrease in drainage and flank pain may indicate obstruction in the urinary tract. Other complications to be watched for include retroperitoneal bleeding, infection, delayed allergic reaction, and pneumothorax or hemothorax.

If the patient goes home with the catheter in place, instruction in self-care is necessary. The patient and family will need to know how to care for the incision site and the urine collection device. They should be taught how to note and record urine volume and evaluate its color and to report to the physician any leakage of urine from the incision site that persists after four days. They also will need to report any symptoms of infection, development of pain, or bright red hematuria. The importance of taking antibiotics precisely as prescribed is stressed. Antibiotic therapy is usually continued for two weeks after surgery. If no complications develop, the patient is able to return to normal daily activities within a week after drainage stops.

After surgery the vital signs are monitored to detect evidence of bleeding or infection. Some bright red blood in the urine passing through the nephrostomy can be expected for one to three days, but the amount of blood should gradually diminish. As bleeding subsides the urine becomes smoky and tinged with old blood. The kidney is a highly vascular organ and postoperative hemorrhage is always a threat.

If the patient has either a Foley catheter or a ureteral catheter or both remaining in place after surgery, they must be kept open and draining. Irrigations, if ordered, are done gently to avoid excessive bleeding. A decrease in drainage and flank pain may indicate obstruction in the urinary tract. Other complications to be watched for include retroperitoneal bleeding, infection, delayed allergic reaction, and pneumothorax or hemothorax.

If the patient goes home with the catheter in place, instruction in self-care is necessary. The patient and family will need to know how to care for the incision site and the urine collection device. They should be taught how to note and record urine volume and evaluate its color and to report to the physician any leakage of urine from the incision site that persists after four days. They also will need to report any symptoms of infection, development of pain, or bright red hematuria. The importance of taking antibiotics precisely as prescribed is stressed. Antibiotic therapy is usually continued for two weeks after surgery. If no complications develop, the patient is able to return to normal daily activities within a week after drainage stops.

Miller-Keane Encyclopedia and Dictionary of Medicine, Nursing, and Allied Health, Seventh Edition. © 2003 by Saunders, an imprint of Elsevier, Inc. All rights reserved.

lith·o·trip·sy

(lith'ō-trip'sē),The crushing of a stone in the renal pelvis, calyces, ureter, or bladder, by mechanical force, laser, or focused sound energy.

Synonym(s): lithotrity

[litho- + G. tripsis, a rubbing]

Farlex Partner Medical Dictionary © Farlex 2012

lithotripsy

(lĭth′ə-trĭp′sē)n. pl. lithotrip·sies

Pulverization of kidney stones or gallstones by means of a lithotripter.

The American Heritage® Medical Dictionary Copyright © 2007, 2004 by Houghton Mifflin Company. Published by Houghton Mifflin Company. All rights reserved.

lithotripsy

Shock-wave lithotripsy A nonsurgical, noninvasive method for fractionating renal, and recently, bile tract calculiMcGraw-Hill Concise Dictionary of Modern Medicine. © 2002 by The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc.

lith·o·trip·sy

(lith'ō-trip-sē)The crushing of a stone in the renal pelvis, ureter, or bladder, by mechanical force or sound waves.

Synonym(s): lithotrity.

Synonym(s): lithotrity.

[litho- + G. tripsis, a rubbing]

Medical Dictionary for the Health Professions and Nursing © Farlex 2012

lithotripsy

(lith'o-trip?se) [ litho-+ Gr. tripsis, rubbing]1. The use of sound waves to fragment or crush stones obstructing the bladder, gallbladder, ureter, or urinary bladder.

2. The production of shock waves by use of an external energy source in order to crush renal stones. Synonym: lithotrity

EXTRACORPOREAL SHOCK WAVE LITHOTRIPSY: Shock waves are transmitted through water to break up gallstones. A. Position for stones in gallbladder. Patient is lying on a fluid-filled bag; B. Position for stones in common bile duct. Patient is in a water bath.

EXTRACORPOREAL SHOCK WAVE LITHOTRIPSY: Shock waves are transmitted through water to break up gallstones. A. Position for stones in gallbladder. Patient is lying on a fluid-filled bag; B. Position for stones in common bile duct. Patient is in a water bath.

extracorporeal shock-wave lithotripsy

Abbreviation: ESWLThe fragmentation of kidney stones with an extracorporeal shock-wave lithotriptor.

See: illustrationMedical Dictionary, © 2009 Farlex and Partners

lithotripsy

A method of fragmenting stones in the urinary system and in the gall bladder, by focused and concentrated ultrasonic shock waves. High energy ultrasound waves, generated by a high-voltage spark discharge, can be focused to a point by parabolic reflectors and aimed so that the point of focus coincides with the stone. The stone shatters and is reduced to particles small enough to be passed naturally in the urine or into the bile duct and bowel. Up to 90% of stones, which previously could have been removed only by open surgery, can now be dealt with by this method.Collins Dictionary of Medicine © Robert M. Youngson 2004, 2005

Latest Searches:

Voraxaze - Voranil - Voorhoeve - voodoo - VOO - Vontrol - von - vomitus - vomiturition - vomitory - vomitoria - vomito - vomitive - vomiting - vomit - vomica - vomerovaginalis - vomerovaginal - vomerorostralis - vomerorostral -

- Service manuals - MBI Corp