Medical term:

infarction

infarction

[in-fark´ shun]in·farc·tion

(in-fark'shŭn),infarction

(ĭn-färk′shən)infarction

Medtalk Dying of tissue, necrosisin·farc·tion

(in-fahrk'shŭn)infarction

(in-fark'shon) [ infarct]aborted myocardial infarction

cardiac infarction

Myocardial infarction.cerebral infarction

See: cerebral infarctexercise-related myocardial infarction

lacunar infarction

malignant cerebral artery infarction

myocardial infarction

Abbreviation: MIAcute MI affects 1.1 million people each year, and approx. 350,000 of them die. The probability of dying from MI is related to the patient's underlying health, whether arrhythmias such as ventricular fibrillation or ventricular tachycardia occur, and how rapidly the patient seeks medical attention and receives appropriate therapies (such as thrombolytic drugs, angioplasty, antiplatelet drugs, beta blockers, and intensive electrocardiographic monitoring). See: illustration; advanced cardiac life support; atherosclerosis; cardiac arrest; sudden death

Etiology

Proven risk factors for MI are tobacco use, diabetes mellitus, abnormally high cholesterol levels, high blood pressure, gender, advanced age, obesity, physical inactivity, chronic kidney disease, a family history of MI at an early age, and loss of albumin in the urine. Some research suggests that high C reactive protein levels, and other conditions may also lead to increased risk.

Symptoms

Classic symptoms of MI in men are a gradual onset of pain or pressure, felt most intensely in the center of the chest, radiating into the neck, jaw, shoulders, or arms, and lasting more than a half hour. Pain typically is dull or heavy rather than sharp or stabbing, and often is associated with difficult breathing, nausea, vomiting, and profuse sweating. Clinical presentations, however, vary considerably, and distinct presentations are seen in woman and the elderly, in whom, e.g., unexplained breathlessness is often the primary symptom. Many patients may mistake their symptoms for indigestion, intestinal gas, or muscular aches. About a third of all MIs are clinically silent, and almost half present with atypical symptoms. Often patients suffering MI have had angina pectoris for several weeks before and simply did not recognize it.

Diagnosis

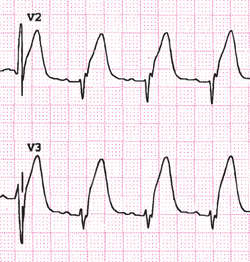

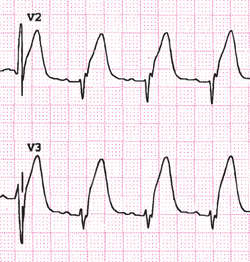

A compatible history associated either with segment elevation (on a 12-lead electrocardiogram) or with elevated blood levels of cardiac muscle enzymes such as troponins or creatine kinase can establish the diagnosis. An ST-segment elevation of more than 1 mm above baseline in at least two contiguous precordial leads or two adjacent limb leads suggests myocardial injury. Myocardial infarctions with this presentation are known as ST-segment elevation MI (STEMI). This finding usually indicates significant muscle damage in the infarct area, a poorer prognosis, and a higher incidence of complications (arrhythmias, cardiogenic shock) than in a non-ST-segment elevation MI (NSTEMI). The differential diagnosis of chest pain must always be carefully considered because other serious illnesses, such as pulmonary embolism, pericarditis, aortic dissection, esophageal rupture, acute cholecystitis, esophagitis, or splenic rupture may mimic MI.

Treatment

Myocardial infarction is a medical emergency; diagnosis and treatment should not be delayed. People who experience symptoms suggestive of MI should be taught to call 911 immediately and chew and swallow aspirin. Oxygen is administered at 4 L/min as soon as it is available. History is gathered throughout the first few minutes after admission even as a 12-lead ECG is being done and blood taken for biomarkers. Cardiac troponins may not become elevated until 4 or more hr after symptoms begin. If the patient is hypotensive or in cardiogenic shock, right-sided ECG leads are assessed for a right ventricular (RV) infarct. An intravenous access is established along with continuous cardiac monitoring, and medications (which may include chewed aspirin [162 to 325 mg], heparins, or other medications to inhibit platelet aggregation, nitroglycerin [given SL, sprayed or IV], IV morphine, and beta-blockers) are administered as prescribed. Pain is assessed on a 1 to 10 intensity scale, and morphine 2 to 10 mg administered IV, with incremental doses of 2 to 8 mg every 5 to 15 min until relief is obtained. Beta-blockers (such as metoprolol or atenolol) decrease myocardial oxygen demand, helping to limit the amount of heart muscle damaged. An IV beta-blocker should be given if the patient is hypertensive or has a tachyarrhythmia as long as no contraindications exist. Patients with STEMI who arrive at the hospital within 6 hr of the onset of symptoms are treated with fibrinolytic therapy or percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI). The goal for administration of fibrinolytic therapy is 30 min postsymptom onset (door-to-needle); for PCI 90 min (door-to-balloon inflation). Absolute contraindications of fibrinolytic therapy include previous intracranial hemorrhage or ischemic stroke within 3 months ( intracranial malignancy), active bleeding, or bleeding disorders (except menses), significant closed head or facial trauma within 3 months (known structural cerebral vascular lesions), and suspected aortic dissection. Reperfusion is the immediate goal, usually best accomplished with balloon angioplasty and endovascular stent placement, although emergency coronary bypass surgery may be needed in cases when PCI fails. An angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitor is administered within 24 hr of a STEMI to suppress the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system and prevent excess fluid retention. ACE inhibitors also prevent conversion of angiotensin I to angiotensin II (a potent vasoconstrictor), thus reducing afterload to help prevent heart failure.

In MI complicated by pulmonary edema, diuretics are administered, and dobutamine infusions may be necessary to increase cardiac output. Strict glucose control (maintaining blood sugars below 150 mg/dl, and preferably in the normal range) reduces mortality in acute MI. Hypotension and circulatory collapse frequently occur in patients with significant RV infarctions, and fluid challenge is administered to optimize RV preload. If this is unsuccessful, the patient with an RV infarct will require inotropic support, correction of bradycardia, and measures to achieve atrioventricular synchrony (cardioversion for atrial fibrillation, etc). In patients with ventricular arrhythmias, defibrillation, or cardioversion, lidocaine, vasopressin, or amiodarone infusions, or other drugs, may be necessary. Anemic patients (hematocrit less than 30 or those actively bleeding) benefit from blood (packed red cell) transfusions.

With contemporary care, about 95% of patients with acute MI who arrive at the hospital in time will survive. These patients are referred to nutrition therapists to learn how to use low-fat, low-cholesterol diets, and to cardiac rehabilitation programs for exercise training, tobacco cessation, and psychosocial support.

Patient care

Acute Care: On admission, all diagnostic and treatment procedures are explained briefly to reduce stress and anxiety. Continuous electrocardiographic monitoring is used to identify changes in heart rhythm, rate, and conduction. Location, radiation, quality, severity, and frequency of chest pain are documented and relieved with IV morphine. Bleeding is the most common complication of antiplatelet, anticoagulant, and fibrinolytic therapies. The complete blood count, prothrombin time, and activated partial thromboplastin time are monitored at daily intervals. IV sites are assessed for evidence of bleeding. Fluid balance and pulmonary status are closely monitored for signs of fluid retention and overload. Breath sounds are auscultated for crackles (which may resolve by having the patient cough when caused by atelectasis, or which may indicate pulmonary edema when they do not). Heart sounds are auscultated for S3 or S4 gallops or new heart murmurs. Patient care and other activities should be organized to allow for periods on uninterrupted rest. Stool softeners are prescribed to prevent straining during defecation, which can cause vagal stimulation and slow the heart rate. Antiembolism stockings help to prevent venostasis and deep vein thrombosis. Emotional support is provided to decrease stress and anxiety. Adjustment disorders and depression are often experienced by MI patients, and the patient and family are assisted to deal with these feelings. Stress tests, coronary angiography, cardiac imaging procedures, reperfusion techniques, and other interventions are explained. The patient receives assistance in coping with changes in health status and self-concept.

Ambulatory Care: Cardiac rehabilitation begins as soon as the patient is physiologically stable. The goal of cardiac rehabilitation is to have the patient establish a healthy lifestyle that minimizes the risk of another MI. Ambulation is slowly increased, and a low-level treadmill test may be ordered before discharge to determine exercise tolerance and the risk of future heart attacks. Patients are taught not only to measure their pulse but also to assess their response to exercise in terms of fatigue, ease of breathing, and perceived workload. Following discharge, exercise is slowly increased, first while being monitored closely by supervised cardiac rehabilitation, and then more independently. The patient also receives information about a low saturated fat, low cholesterol, low calorie diet, such as the DASH eating plan (Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension), resumption of sexual activity, work, and other activities. The patient is taught about desired and adverse affects of all medications: aspirin therapy is usually prescribed as ongoing antiplatelet therapy (with or without clopidogrel), but patients should be warned about the risk of bleeding and be advised to avoid products containing ibuprofen, which blocks aspirin’s antiplatelet effects. Smoking cessation is an important preventive for future MIs. High blood pressure, obesity, adverse cholesterol levels, and diabetes mellitus also should be carefully managed to help prevent future MIs. Alcohol intake should be limited to 1 drink daily (women), 2 drinks daily (men). Opportunities are created for patients and families to share feelings and receive realistic reassurance about common fears.

placental infarction

pulmonary infarction

silent myocardial infarction

infarction

The deprivation of a part of a tissue or organ of its blood supply so that a wedge-shaped area of dead tissue (an infarct) forms. Infarction of part of the heart muscle is the process underlying a heart attack.Infarction

in·farc·tion

(in-fahrk'shŭn)Synonym(s): infarct.

infarction

[in-fark´ shun]in·farc·tion

(in-fark'shŭn),infarction

(ĭn-färk′shən)infarction

Medtalk Dying of tissue, necrosisin·farc·tion

(in-fahrk'shŭn)infarction

(in-fark'shon) [ infarct]aborted myocardial infarction

cardiac infarction

Myocardial infarction.cerebral infarction

See: cerebral infarctexercise-related myocardial infarction

lacunar infarction

malignant cerebral artery infarction

myocardial infarction

Abbreviation: MIAcute MI affects 1.1 million people each year, and approx. 350,000 of them die. The probability of dying from MI is related to the patient's underlying health, whether arrhythmias such as ventricular fibrillation or ventricular tachycardia occur, and how rapidly the patient seeks medical attention and receives appropriate therapies (such as thrombolytic drugs, angioplasty, antiplatelet drugs, beta blockers, and intensive electrocardiographic monitoring). See: illustration; advanced cardiac life support; atherosclerosis; cardiac arrest; sudden death

Etiology

Proven risk factors for MI are tobacco use, diabetes mellitus, abnormally high cholesterol levels, high blood pressure, gender, advanced age, obesity, physical inactivity, chronic kidney disease, a family history of MI at an early age, and loss of albumin in the urine. Some research suggests that high C reactive protein levels, and other conditions may also lead to increased risk.

Symptoms

Classic symptoms of MI in men are a gradual onset of pain or pressure, felt most intensely in the center of the chest, radiating into the neck, jaw, shoulders, or arms, and lasting more than a half hour. Pain typically is dull or heavy rather than sharp or stabbing, and often is associated with difficult breathing, nausea, vomiting, and profuse sweating. Clinical presentations, however, vary considerably, and distinct presentations are seen in woman and the elderly, in whom, e.g., unexplained breathlessness is often the primary symptom. Many patients may mistake their symptoms for indigestion, intestinal gas, or muscular aches. About a third of all MIs are clinically silent, and almost half present with atypical symptoms. Often patients suffering MI have had angina pectoris for several weeks before and simply did not recognize it.

Diagnosis

A compatible history associated either with segment elevation (on a 12-lead electrocardiogram) or with elevated blood levels of cardiac muscle enzymes such as troponins or creatine kinase can establish the diagnosis. An ST-segment elevation of more than 1 mm above baseline in at least two contiguous precordial leads or two adjacent limb leads suggests myocardial injury. Myocardial infarctions with this presentation are known as ST-segment elevation MI (STEMI). This finding usually indicates significant muscle damage in the infarct area, a poorer prognosis, and a higher incidence of complications (arrhythmias, cardiogenic shock) than in a non-ST-segment elevation MI (NSTEMI). The differential diagnosis of chest pain must always be carefully considered because other serious illnesses, such as pulmonary embolism, pericarditis, aortic dissection, esophageal rupture, acute cholecystitis, esophagitis, or splenic rupture may mimic MI.

Treatment

Myocardial infarction is a medical emergency; diagnosis and treatment should not be delayed. People who experience symptoms suggestive of MI should be taught to call 911 immediately and chew and swallow aspirin. Oxygen is administered at 4 L/min as soon as it is available. History is gathered throughout the first few minutes after admission even as a 12-lead ECG is being done and blood taken for biomarkers. Cardiac troponins may not become elevated until 4 or more hr after symptoms begin. If the patient is hypotensive or in cardiogenic shock, right-sided ECG leads are assessed for a right ventricular (RV) infarct. An intravenous access is established along with continuous cardiac monitoring, and medications (which may include chewed aspirin [162 to 325 mg], heparins, or other medications to inhibit platelet aggregation, nitroglycerin [given SL, sprayed or IV], IV morphine, and beta-blockers) are administered as prescribed. Pain is assessed on a 1 to 10 intensity scale, and morphine 2 to 10 mg administered IV, with incremental doses of 2 to 8 mg every 5 to 15 min until relief is obtained. Beta-blockers (such as metoprolol or atenolol) decrease myocardial oxygen demand, helping to limit the amount of heart muscle damaged. An IV beta-blocker should be given if the patient is hypertensive or has a tachyarrhythmia as long as no contraindications exist. Patients with STEMI who arrive at the hospital within 6 hr of the onset of symptoms are treated with fibrinolytic therapy or percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI). The goal for administration of fibrinolytic therapy is 30 min postsymptom onset (door-to-needle); for PCI 90 min (door-to-balloon inflation). Absolute contraindications of fibrinolytic therapy include previous intracranial hemorrhage or ischemic stroke within 3 months ( intracranial malignancy), active bleeding, or bleeding disorders (except menses), significant closed head or facial trauma within 3 months (known structural cerebral vascular lesions), and suspected aortic dissection. Reperfusion is the immediate goal, usually best accomplished with balloon angioplasty and endovascular stent placement, although emergency coronary bypass surgery may be needed in cases when PCI fails. An angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitor is administered within 24 hr of a STEMI to suppress the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system and prevent excess fluid retention. ACE inhibitors also prevent conversion of angiotensin I to angiotensin II (a potent vasoconstrictor), thus reducing afterload to help prevent heart failure.

In MI complicated by pulmonary edema, diuretics are administered, and dobutamine infusions may be necessary to increase cardiac output. Strict glucose control (maintaining blood sugars below 150 mg/dl, and preferably in the normal range) reduces mortality in acute MI. Hypotension and circulatory collapse frequently occur in patients with significant RV infarctions, and fluid challenge is administered to optimize RV preload. If this is unsuccessful, the patient with an RV infarct will require inotropic support, correction of bradycardia, and measures to achieve atrioventricular synchrony (cardioversion for atrial fibrillation, etc). In patients with ventricular arrhythmias, defibrillation, or cardioversion, lidocaine, vasopressin, or amiodarone infusions, or other drugs, may be necessary. Anemic patients (hematocrit less than 30 or those actively bleeding) benefit from blood (packed red cell) transfusions.

With contemporary care, about 95% of patients with acute MI who arrive at the hospital in time will survive. These patients are referred to nutrition therapists to learn how to use low-fat, low-cholesterol diets, and to cardiac rehabilitation programs for exercise training, tobacco cessation, and psychosocial support.

Patient care

Acute Care: On admission, all diagnostic and treatment procedures are explained briefly to reduce stress and anxiety. Continuous electrocardiographic monitoring is used to identify changes in heart rhythm, rate, and conduction. Location, radiation, quality, severity, and frequency of chest pain are documented and relieved with IV morphine. Bleeding is the most common complication of antiplatelet, anticoagulant, and fibrinolytic therapies. The complete blood count, prothrombin time, and activated partial thromboplastin time are monitored at daily intervals. IV sites are assessed for evidence of bleeding. Fluid balance and pulmonary status are closely monitored for signs of fluid retention and overload. Breath sounds are auscultated for crackles (which may resolve by having the patient cough when caused by atelectasis, or which may indicate pulmonary edema when they do not). Heart sounds are auscultated for S3 or S4 gallops or new heart murmurs. Patient care and other activities should be organized to allow for periods on uninterrupted rest. Stool softeners are prescribed to prevent straining during defecation, which can cause vagal stimulation and slow the heart rate. Antiembolism stockings help to prevent venostasis and deep vein thrombosis. Emotional support is provided to decrease stress and anxiety. Adjustment disorders and depression are often experienced by MI patients, and the patient and family are assisted to deal with these feelings. Stress tests, coronary angiography, cardiac imaging procedures, reperfusion techniques, and other interventions are explained. The patient receives assistance in coping with changes in health status and self-concept.

Ambulatory Care: Cardiac rehabilitation begins as soon as the patient is physiologically stable. The goal of cardiac rehabilitation is to have the patient establish a healthy lifestyle that minimizes the risk of another MI. Ambulation is slowly increased, and a low-level treadmill test may be ordered before discharge to determine exercise tolerance and the risk of future heart attacks. Patients are taught not only to measure their pulse but also to assess their response to exercise in terms of fatigue, ease of breathing, and perceived workload. Following discharge, exercise is slowly increased, first while being monitored closely by supervised cardiac rehabilitation, and then more independently. The patient also receives information about a low saturated fat, low cholesterol, low calorie diet, such as the DASH eating plan (Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension), resumption of sexual activity, work, and other activities. The patient is taught about desired and adverse affects of all medications: aspirin therapy is usually prescribed as ongoing antiplatelet therapy (with or without clopidogrel), but patients should be warned about the risk of bleeding and be advised to avoid products containing ibuprofen, which blocks aspirin’s antiplatelet effects. Smoking cessation is an important preventive for future MIs. High blood pressure, obesity, adverse cholesterol levels, and diabetes mellitus also should be carefully managed to help prevent future MIs. Alcohol intake should be limited to 1 drink daily (women), 2 drinks daily (men). Opportunities are created for patients and families to share feelings and receive realistic reassurance about common fears.

placental infarction

pulmonary infarction

silent myocardial infarction

infarction

The deprivation of a part of a tissue or organ of its blood supply so that a wedge-shaped area of dead tissue (an infarct) forms. Infarction of part of the heart muscle is the process underlying a heart attack.Infarction

in·farc·tion

(in-fahrk'shŭn)Synonym(s): infarct.

Latest Searches:

Voraxaze - Voranil - Voorhoeve - voodoo - VOO - Vontrol - von - vomitus - vomiturition - vomitory - vomitoria - vomito - vomitive - vomiting - vomit - vomica - vomerovaginalis - vomerovaginal - vomerorostralis - vomerorostral -

- Service manuals - MBI Corp